Posted on March 31, 2020

Summary

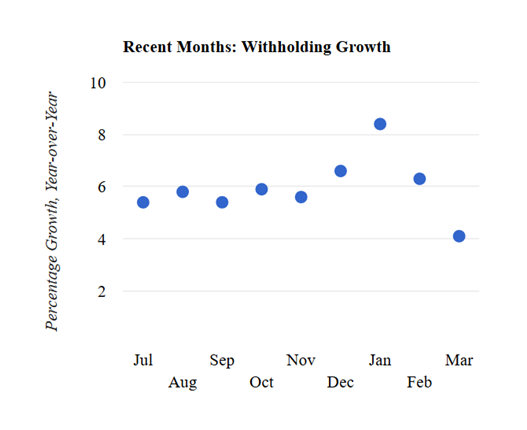

- Withholding growth in March dropped significantly, consistent with the economy currently being in recession.

- We’re in the week-long period that occurs each month in which we cannot get reliable measures of withholding growth because of calendar effects.

- When we start measuring withholding growth again next week, we’ll be adjusting the measure to remove the estimated effect of recent tax law changes affecting withholding.

It’s not a surprise: we measure that in March there was a significant decline in the growth of income and payroll tax amounts withheld from paychecks and remitted to the Treasury Department. We estimate that withholding growth fell from 6.3 percent in February—measured relative to the amounts in February of a year ago—to 4.1 percent in March. As I posted last week, such drops in the past have typically, but not always, indicated that the economy was in recession. When a year-over-year measure of growth drops, it implies a much larger drop in the amount relative to the prior month—unless the measure of growth exactly 12 months prior was unusually high; this time, of course, it’s March of this year that has been terribly unusual, not last March. The drop in withholding growth follows a period in which it had been very stable, measuring between 5.5 percent and 6 percent for each month from July to November of last year, before temporarily rising in December and especially so in January during bonus season (when withholding growth often temporarily moves off trend), but then returning most of the way back in February (see chart above). That the withholding data are consistent with the economy being in recession should come as no surprise given the far-reaching economic disruptions from the efforts to contain the spread of the novel coronavirus.

We now are in the normal week-long period at the very end and beginning of each month in which we cannot measure withholding growth. That results because the calendar effects at that time are very difficult to appropriately filter (see methodology).

When we begin getting withholding growth measures again next week, we’ll be adjusting the amount to remove the estimated effects of the withholding tax law changes enacted last week. The main such change allows businesses, for the rest of the calendar year, to delay remitting their share of Social Security payroll taxes, which should have a very significant effect on withholding (see previous post). We want to measure withholding growth on a constant law basis so that we can draw the connection from withholding, the data for which are available very quickly, to economywide wages, the data for which are available much more slowly. Because we’ll be using estimates of the effects of the law changes, that will add some uncertainty to the estimates of withholding growth on a constant law basis. Tax law changes significantly affecting withholding have occurred during about one-third of the period since 2005 that we track, and during those periods the estimates of withholding growth on a constant law basis continued to conform to wage growth. The recently enacted changes in withholding, however, are much larger than what we have seen in the past; we will be assessing the effects of the payment delays in retrospect.