Posted April 28, 2020

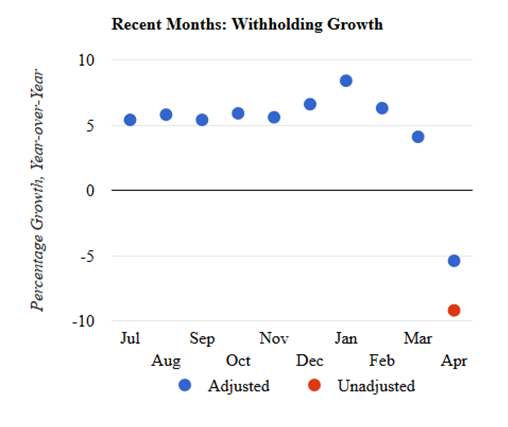

- We estimate that tax withholding on a constant law basis fell by 5.4 percent in April compared to amounts from a year ago, a very large change from the 6 percent increase registered just two months ago in February. That almost 11.5 percentage point swing is consistent with about a 10.5 percent drop in withholding between February and April. Movements in withholding tend to track economywide wages.

- Declines in withholding of that amount are much more rapid than was experienced in the Great Recession and are in line with what some economists are projecting for near-term declines in GDP.

- Those declines in withholding would have been larger if we did not adjust the actual withholding amounts in April to remove the estimated effect on payroll tax withholding of legislation enacted in March. We have, however, reduced that adjustment since earlier this month to reflect more recent information about the effect of remittance delays allowed by the CARES Act.

We estimate that the amount of tax withholding in April fell by 5.4 percent compared to the amount in April of a year ago, a rapid and very large swing from the (positive) 6 percent year-over-year growth recorded in February and 4.1 percent registered in March. The swing of almost 11.5 percentage points in that year-over-year measure–over just a two-month period–is consistent with about a 10.5 percent drop in withholding between February and April. The two-month decline is almost three times bigger than the worst of what we estimated for any two months during the Great Recession. Note that the April drop is adjusted to remove our estimate of the effect of certain payroll tax changes enacted last month–remittance delays allowed by the CARES Act and payroll tax credits provided by earlier legislation. Withholding without the adjustment dropped by 9.2 percent in April (year-over-year), of which 3.8 percent is attributed to the tax law changes (see chart below). That leaves a 5.4 percent decline on a constant law basis, reflecting underlying economic conditions, most importantly economywide wages.

A drop of about 10.5 percent in withholding between February and April is roughly in line with what some economists are foreseeing for overall economic growth in the near term. For example, the Congressional Budget Office last week released preliminary projections that real GDP will decline by about 12 percent during the current April-June quarter, compared to the January-March quarter. That 12 percent decline is not annualized: it is just the pure quarter-to-quarter drop in real GDP, which is comparable to the 10.5 percent drop in withholding estimated from February to April. We can see how CBO and some other economic forecasters are projecting declines in real GDP in the second quarter, on an annualized basis, in the vicinity of 40 percent. Annualized growth rates, though, may not be all that meaningful in measuring an economy in which major parts come grinding to a halt such as in the current environment.

Our monthly measure of withholding growth tends to track closely with the wage measure included in the monthly employment report of the Bureau of Labor Statistics; the employment release for April is scheduled for Friday, May 8. For March, at the beginning of the downturn, BLS estimated that wages grew by about 3 percent on a year-over-year basis, which was lower by 1-2 percentage points than in the previous month; the comparable withholding growth measure for March was about 4 percent, about 2 percentage points less than in the previous month. We’ll see if the BLS report for April has wages dropping anywhere near the 5 percent year-over-year decline in withholding that we estimate.

On a technical note, we adjust the decline in withholding to remove the estimated effect of provisions of the CARES Act that allow some withholding payment delays (along with employment tax credits enacted earlier in March). The CARES Act, enacted in late March, allows firms to hold off remitting to the Treasury their share of Social Security payroll taxes that would otherwise be due through the rest of the calendar year; the remittances themselves can then be delayed for a year or two after that, to the end of 2021 or 2022. By adjusting withholding to remove the effect of the delayed payments and the changes to credits, we estimate withholding on a constant law basis, which allows us to draw the link to wages (which are not directly affected by those law changes).

For even more technical detail (please excuse the long paragraph), we have reduced our estimate of the upfront revenue-reducing effect of those payroll tax changes from about 15 percent of withholding to about 8 percent, a substantial cut. At the beginning of this month, right after enactment of the CARES Act, we hewed closely to the estimates of the Joint Committee on Taxation, which we believe assumed most all firms would delay their payments to the extent possible in order to get an interest free loan from the government. That made sense and that agency’s estimates are highly reliable. However, many financial analysts are advising firms to closely consider their specific circumstances before delaying the payment, which led us to reduce the effect substantially. First, employees are concerned that their firms might not have sufficient funds on hand to make the remittances when eventually due at the end of 2021 or 2022, which could involve personal liability. In addition, a more economic issue involves an interaction with the more generous use of business losses allowed by the CARES Act. Because the new law allows businesses to use losses in 2020 (or already logged in 2019 and 2018) to receive refunds of taxes paid up to five years prior, paying the Social Security payroll taxes in 2020 could allow, pending further guidance from Treasury, an accelerated tax deduction in 2020 that would be more valuable than an interest free loan. In particular, for firms expecting to be in a loss position in 2020—and unfortunately there will be a lot of that—they may well benefit more by paying the payroll taxes and taking the corresponding deduction in 2020, generating greater losses in that year and getting a so-called carryback refund of up to 35 percent of that amount (for corporations, if applied to years before the corporate tax rate cuts that took effect in 2018). That strategy could be more beneficial than deferring the payment of the taxes, keeping a separate account for the funds, investing those funds in safe assets until the remittances are due, and then getting a deduction in a year with the current 21 percent corporate tax rate. For firms in a loss position in both 2020 and 2021, not delaying the remittances could be even more beneficial.