Posted on July 31, 2020

Summary

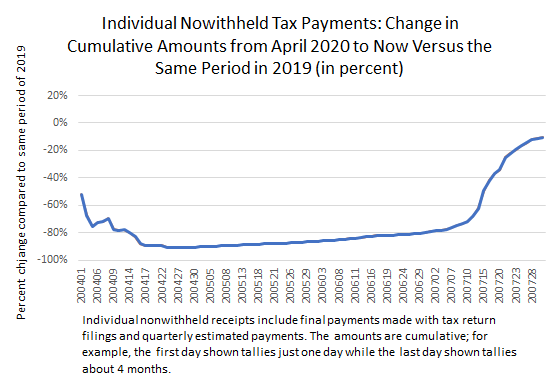

- Nonwithheld tax receipts, which include final payments with tax returns and quarterly estimated payments, boomed in July, but only because of payments that were allowed to be delayed from April and June.

- Looking more appropriately over the April-July period, which was largely unaffected by the payment delays, nonwithheld payments appear to be down by about 10 percent compared to the April-July period of 2019.

- It is likely that both quarterly payments and final payments were down this year compared to year-ago amounts, but the separate tabulations for those two components are not made publicly available by the Treasury Department.

As we’ve discussed previously, federal receipts from individual income taxes have boomed in July, but only because amounts normally paid in April and June were allowed to be paid in July this year. Nonwithheld receipts this July include final payments with tax return filings for 2019, normally due in April, and two quarterly estimated payments normally due in April and June. The IRS is now pretty much finished with counting the money paid with tax return filings, so we can assess the results with little chance of the story being significantly changed by further processing of tax returns filed earlier this month.

Nonwithheld receipts from April through July this year look to be down by about 10 percent compared to the same period last year (see the chart below for the daily tabulation, using data from the Treasury Department’s Daily Treasury Statements, with the last data point representing nearly the full 4-month change). Comparing the four-month period between years allows us to get an apples-to-apples comparison, because the tally in both years includes final payments and two quarterly estimated payments. But we cannot tell how much of the decline is from amounts due with 2019 tax returns and how much is from weak quarterly payments for the 2020 tax year.

Can we tell anything about the separate movements in quarterly payments and final payments? Well, we know that final payments with tax returns are larger than quarterly estimated payments, even normally the sum of two of them, so we can guess that final payments were probably down from last year’s amounts. If final payments are normally roughly 70 percent of total nonwithheld payments over the April-July period, my rough estimate, then it’s hard to see how final payments this year could be unchanged or higher than those paid last year; otherwise it would take a very big decline in quarterly payments to alone account for the 10 percent decline in nonwithheld receipts. If that 70 percent rule of thumb holds, then quarterly payments would need to have declined by about 33 percent if final payments were unchanged from 2019 amounts.

Quarterly payments could certainly be down substantially because of the economic downturn, but probably not enough to solely explain the drop in nonwithheld receipts for two reasons. First, economywide personal income in recent months hasn’t fallen by anywhere near 33 percent compared to year-ago amounts–even with the sharp economic contraction. In addition, estimated payments tend to be somewhat unresponsive to current economic developments, leaving taxpayers with large tax amounts due or refunds when they file their tax returns–the reason why final payments are notoriously difficult for federal and state revenue analysts to forecast accurately. Quarterly estimated payments tend to be somewhat unresponsive to economic developments at least in part because many higher-income taxpayers tell their accountants to simply pay the minimum amount necessary in order for the taxpayer to avoid future penalties when filing tax returns for the year, rather than telling the accountants to monitor the taxpayer’s capital gains, wages, partnership income, and other sources of taxable income. This year could be somewhat different, though, as many taxpayers are forced to monitor their finances more closely than usual. Unfortunately, data on the split of monthly nonwithheld tax receipts between estimated and final payments is not made publicly available. We may, however, be able to very roughly infer the split once we get the September quarterly payment, if we assume that the September payment behaves like the April and June ones.