Posted on March 31, 2021

Summary

- Tax withholding growth in March was strong on both a year-over-year basis and, more relevantly, on a year-over-two-year basis. We now look at two-year growth in withholding because the standard year-over-year measures are becoming distorted by the base period being the severely depressed amounts from a year ago.

- Withholding was so strong in March that it makes it look like tax withholding, and therefore the amount of economywide wages and salaries, is more than fully recovered from the recession. That sounds strange and highly unlikely given that there is still a lot of unemployment, and current, direct measures of wages and salaries are not growing nearly as fast.

- There are a number of possible explanations for the fast growth in withholding, including disproportionately high growth in wages for middle- and higher-income workers, who pay the bulk of the income tax and thus are over-represented in the withholding data; and a faster rebound in economywide wages and salaries than is indicated in current, direct measures from samples of firms.

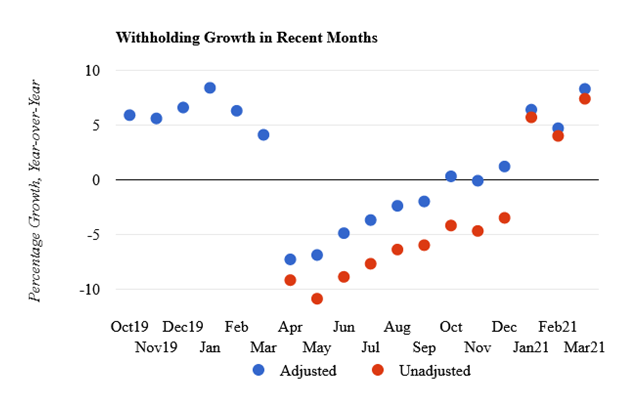

We measure that tax withholding jumped in March to 8.3 percent above the amount from March of 2020, adjusted to remove the effects of tax law changes that affect withholding (but not wages and salaries) and to standardize the makeup of business days across months (see chart below). Without the tax law adjustments (the unadjusted points in the chart), withholding growth was just bit lower, at 7.4 percent. We measured such growth in February on the adjusted basis at 4.7 percent, which was itself a big improvement over amounts from around the end of 2020, and in January at 6.4 percent, which is a volatile month with often temporary movements because of year-end bonuses. Part of the reason for the jump in March above the growth of previous months is that withholding in March of a year ago had begun to drop as a result of the effects of the pandemic. Withholding in March 2020 was 4.1 percent above March 2019 amounts–that’s the way year-over-year growth is measured–after such growth generally was in the 5.5 percent to 6 percent range for much of the prior year. The year-over-year measures are now clearly being affected by the pandemic, and we can expect such year-over-year measures to show even greater growth in coming months as the comparison month becomes the very depressed levels of last spring and summer. As we discussed in a previous post, year-over-year withholding comparisons are going to become very difficult to interpret in coming months, and we are now introducing the year-over-two-year growth measure for a more intuitive way of assessing withholding performance.

Withholding growth in March looks very strong even on our new year-over-two-year growth basis (see chart below). Compared to the amount of withholding in March 2019, withholding in March 2021 by our measure was 12.8 percent higher, which is an average of about 6.2 percent per year compounded. Measuring withholding growth in this way “skips over” the early part of the pandemic-induced recession. (That 12.8 percent growth can also be measured, mathematically, as the combination of 4.1 percent growth from March 2019 to March 2020, and the 8.3 percent growth from March 2020 to March 2021: 1.041 times 1.083 = 1.128 , with rounding if you actually do that math.) Indeed, such two-year growth had been averaging about 11 percent in the second half of 2019 and hadn’t been as high as the recent 12.8 percent rate for most of the past decade. So, in a way, withholding growth in March was so strong that it makes it look like tax withholding, and therefore the amount of economywide wages and salaries, is not only fully recovered from the recession, but actually is a bit higher than if it had continued moving up since early last year at the same rate as it had in the year before the pandemic. That sounds strange and highly unlikely given that there is still a lot of unemployment, and current, direct measures of wages and salaries are not growing nearly as fast: two-year wage and salary growth in the National Income and Product Accounts was about 5 percent in February, and it was 4 percent in the monthly establishment survey from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. So how could tax withholding be growing so fast?

There are any number of possible explanations for the very strong recent withholding amounts. The first two of the following, and maybe a bit of the third, all acting in some combination, are my most likely candidates:

- Wages and salaries have recovered well for middle- and higher-income workers, those who pay the bulk of the income tax and thus are over-represented in the withholding data, but have recovered less well in general for lower-income individuals. It is clear from other data that middle- and higher-income workers in general have suffered less in this recession than have many lower-income workers. Payroll tax withholding is also included in the measure of total withholding, but only the very highest-income workers earn enough in the January-March period to get above the annual threshold (currently $142,800) above which there is no assessment of Social Security payroll taxes (the biggest part of payroll taxes); thus, the often offsetting distributional effects from Social Security taxes, in which skewing income toward higher-income individuals reduces effective tax rates, is probably not much at play yet in 2021.

- Wages and salaries have rebounded more than is indicated from conventional statistics such as the monthly employment report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). If this is the case, we may not see the confirmation until release of data from the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages–administrative data from most all employers reported for purposes of the federal and state governments administering the unemployment insurance program. Those data are very lagged, with data for the first quarter of 2021 to be released by BLS in partial form in mid-August and then in complete form at the beginning of September.

- The strong withholding growth in recent months that is above the amount reported for economywide wages and salaries could be a temporary anomaly that will go away. Certainly there have been times in the past when withholding amounts did not track wages and salaries as closely as they typically do. That was my thought in January, and partway into February, but not as much now.

- We could be mismeasuring the effects of law changes on withholding. For example, from January-March 2021 we have identified minimal legislative adjustments, reflecting mainly the new employee retention tax credit that did not exist in the January-March period of last year. It’s hard to see how additional unemployment insurance benefits or other such factors could have boosted withholding in the past three months substantially. Part of the reason we have confidence that overall withholding is doing well is specifically because there are limited legislative adjustments to the raw withholding data. Starting in April, we again have more significant legislative adjustments to our measure of year-over-year withholding growth because last year the CARES Act took effect mainly in April, but the provisions with the largest effects on withholding have now expired.

- Other factors could be boosting withholding but not wages and salaries, but I’m hard-pressed to think of any that would be big enough to explain such strength in withholding. For example, there are new withholding forms and tables that apply for new workers (and optionally for existing workers) that went into effect last year, but I might expect those effects on net to reduce withholding overall, because the new forms and tables are set up to better align taxpayers’ withholding and tax amounts and to reduce the prevalent overwithholding (and resulting refunds). And any such effects on withholding should be gradual.

Things to look for in the future are, clearly, whether the jump in withholding on a two-year basis is sustained; whether the BLS monthly employment reports start showing more growth in wages and salaries; and, eventually, what the quarterly BLS data for 2021Q1 show late this summer.