Posted on September 17, 2021

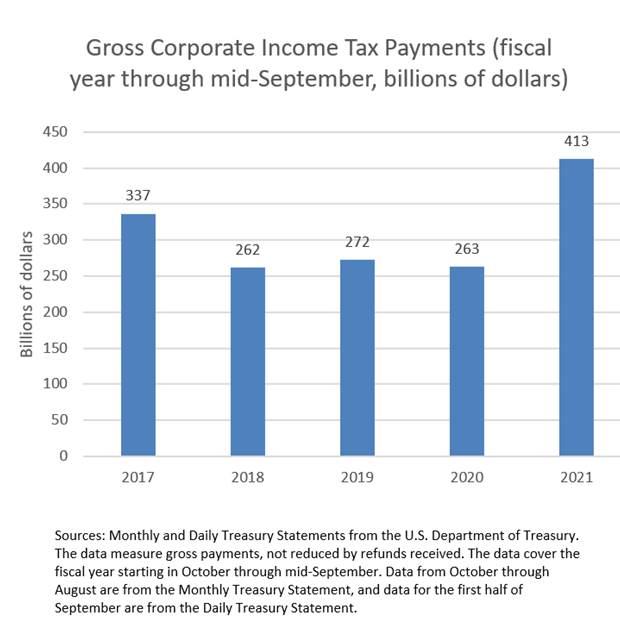

It was no real surprise given the amounts paid in recent months, but the mid-September quarterly payment of income taxes by corporations continued to be very strong. With most all of the September payment now in the books, amounts so far this month have been about 57 percent above payments through the comparable point in September last year, and 44 percent above the comparable amount in September 2019. That guarantees that payments for the federal fiscal year, which concludes at the end of the month, will be well above those not just in 2020, but in pre-pandemic years as well (see chart below). For the fiscal year it looks like gross payments (that is, not net of refunds received by corporations) will be more than 50 percent above the amounts in each of the past three years. They will also be well above those in 2017, even though corporate income tax rates were much higher back then (a top 35 percent rate, before the tax cuts that took effect on January 1, 2018, reduced the top corporate tax rate to 21 percent). The main question is why corporate income tax payments are so high.

We won’t know for a couple of years or more, when data from tax returns for this year become available, what sources of income are responsible for the jump in taxable corporate profits and corporate tax payments. But we can guess at some of the main influences.

- Commodity price inflation has occurred across a range of U.S. products, from agricultural raw materials (such as lumber) to food, metals and energy products. (Some of those price jumps have moderated in recent months, others have not.) The thing about commodity price increases is that those show up pretty directly as increased profits to the producers, as the higher prices get passed along to consumers. For those of you steeped in the details of the National Income and Product Accounts, look no further than the inventory valuation adjustment in recent quarters to see some of the effects. Firms with inventories of these goods are seeing large profits from selling the goods at prices much higher than those they paid for the products.

- Profits have been boosted by subsidies provided to businesses by the federal government as a result of legislation enacted in response to the coronavirus and resulting economic disruption. It’s hard to follow the money, but the subsidies supported firms that paid others, such as employees and suppliers. The subsidies themselves were generally nontaxable to the recipient firms (such as those with Paycheck Protection Program loans that were forgiven), but to some extent the recipient firms paid the amounts to other firms, which would be taxable to them.

- Shifts in profits of firms have probably occurred between the profitable and unprofitable ones. Only profitable firms pay taxes, so to the degree that the pandemic has boosted the profits of certain types of firms and reduced the profits of others, making many newly unprofitable, that could boost tax payments for the same level of net profits in the economy.

- We expect that substantial increases have occurred in capital gains realizations of corporations, boosted by increases in stock prices and increases in trading activity. Payments of individual income taxes with tax return filings boomed in this year’s filing season for 2020 activity, despite the 2020 recession, and we expect that much of that growth occurred from higher-income taxpayers who had large increases in capital gains realizations (see previous post and a blog post I co-authored with folks from the Hamilton Project at the Brookings Institution). Capital gains realizations of corporations correlate with those of individuals.

While corporate tax payments have surged, tax refunds to corporations have not (see chart below). Through almost the entire fiscal year, refunds have remained close to those in recent years. The stability of refunds in 2020 and 2021 compared to earlier years has been a surprise, given the legislation enacted last year that was intended to get large refunds out to corporations. The legislation, which we have discussed several times in previous posts, allowed firms to use losses in 2018 and 2019 (as well as in 2020) to receive refunds of past taxes paid up to five years earlier. Delays by the IRS in processing the refund applications, because many of the refunds required paper processing, have been a problem during the pandemic and could be delaying some refunds even about a year and a half after the legislation was enacted.