Posted on February 2, 2022

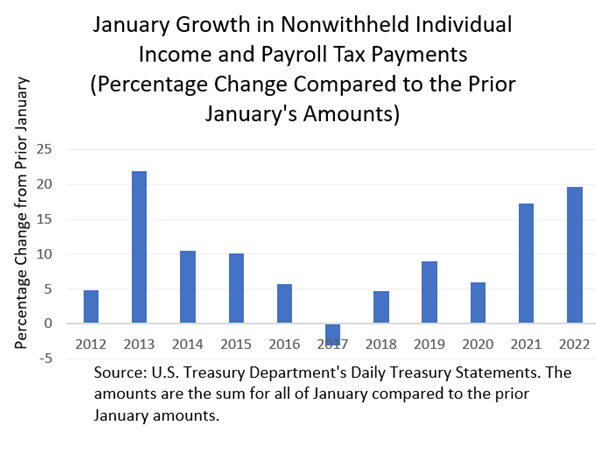

Quarterly estimated payments by individuals of income and payroll taxes continued to move up sharply in January, following strong quarterly payments over the past year. Based on amounts reported by the U.S. Treasury Department in its Daily Treasury Statements, we estimate that total nonwithheld receipts rose from about $125 billion in January 2021 to almost $150 billion in January 2022, an increase of about 20 percent (see chart below). Nonwithheld receipts in January consist largely of the fourth and final quarterly estimated payment for the prior tax year, 2021 in this case; they can also include much smaller amounts of back tax payments for 2020 or earlier tax years and potentially even some small amounts paid at the very end of the month with the earliest tax return filings for 2021. Growth in January of a year ago was also strong, up by 17 percent, so growth over the past two years, measuring back to just before the pandemic affected economic activity, has been about 40 percent, a very high amount of growth.

The robust growth in January estimated payments continues the pattern from last September and June, the previous two quarterly payment months. In September (see previous post) such nonwithheld receipts grew by about 25 percent compared to the amount paid in September 2021. And in June, we reckoned, based on the daily tax payments, that estimated payments were up by slightly more than 40 percent compared to the amount from two years prior, much like in January 2022 compared to January 2020. (We couldn’t make comparisons to receipts in June 2020 because those payments were delayed by IRS action during the early stages of the pandemic.) The jump in estimated payments in January 2022 compared to January 2021 probably reflects at least two factors:

- Strong growth during 2021 of nonwage income of higher-income taxpayers, who make most all of the quarterly estimated payments. In 2019, the last year for which we have data from the IRS, about 96 percent of quarterly estimated payments of individuals were made by those with incomes above $100,000, more skewed even than payments of overall income taxes, for which about 83 percent were made by such higher-income individuals; the number of tax returns filed by those higher-income taxpayers accounted for only about 20 percent of the returns filed by all taxpayers. The nonwage income includes business income from partnerships, sole proprietorships, and other businesses that pass their income through to individuals; capital gains realizations; and dividends.

- The high amount of final payments with tax returns for 2020 filed last spring that caused many taxpayers to raise their estimated payments for 2021. A common tax payment strategy of higher-income taxpayers is to ignore the movements in their quarterly income and instead pay enough over the year in the combination of quarterly estimated taxes and withholding from paychecks to just exceed their prior year’s income tax liability, or 10 percent in excess of their prior year’s income tax liability for taxpayers with adjusted gross income exceeding $150,000. If taxpayers make payments at least that large, then the tax code prohibits underpayment penalties from being assessed regardless of how much taxes are owed when the taxpayer timely files a tax return for the year. That strategy does make final payments and refunds with tax returns very volatile from year to year, as evidenced by surges in overall tax payments with tax filings after certain boom years and typically big drops in those payments after recessions–although after the 2020 pandemic-induced recession, payments with tax returns filed in the spring of 2021 were unusually large (see previous post and research). We have to wait to see the size of payments and refunds during this filing season to see how closely taxpayers’ quarterly payments and withholding lined up with actual taxes owed for 2021.