Posted on May 10, 2020

Summary

- Friday’s BLS employment report for April not surprisingly showed a sharp drop in economywide wages, a steeper drop than indicated by the tax withholding data alone. The two measures tend to move together, though far from in lockstep.

- BLS measures of wage growth for different groups of workers indicate that more of the effects of the wage declines are hitting lower-wage workers. That could be consistent with a steeper drop in wages than in withholding.

There are lots of excellent descriptions out there of the jobs report for April released on Friday by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS, a part of the Department of Labor). I’ll just focus on two things: 1) the big drop in overall wages as measured by the BLS establishment survey, like the big drop recorded in income and payroll tax withholding (which is based on wages), and 2) evidence from the report for a bigger hit to lower-wage workers. Economywide wage growth is not one of the headline numbers coming from the employment report, but it’s there, although with some shortcomings such as being subject to revision, being based on a sample, and measured exclusive of various effects (for example, year-end bonuses).

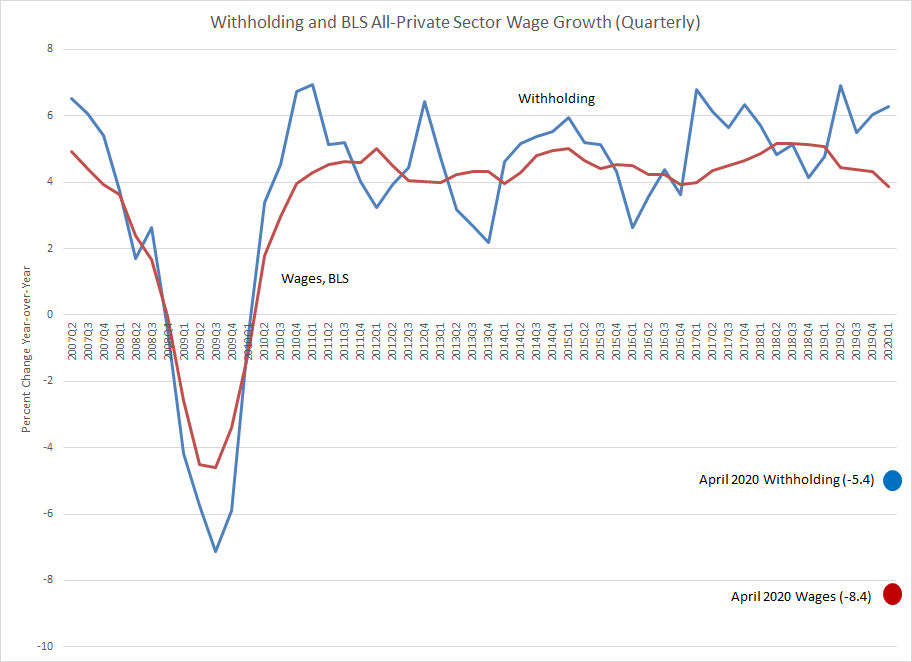

First, overall wages fell more than withholding in April, though both fell sharply. Wages for all private sector workers, as measured by BLS, rose 3.9 percent, year-over-year, in the first quarter of the year (and 3.0 percent in March) but fell 8.4 percent in April. That’s a terrible swing down (see chart below). Withholding tax collections, as we measure them on a constant law basis (so as to draw comparisons with wages), rose 6.3 percent in the first quarter (and 4.1 percent in March) but fell 5.4 percent in April. So, both measures were way down in April. The two measures don’t move in lockstep historically, but they do capture a lot of the same swings. The employment report measure of wages is much more stable, at least in part because it doesn’t take into account year-end bonuses and other irregular income, which can be quite variable. Income distribution shifts can also play a role in why the two measures don’t move in lockstep, and that brings me to my next point.

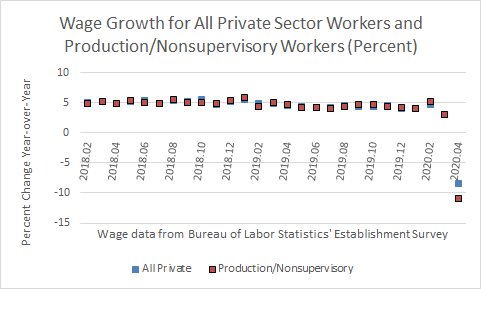

All sorts of information from the BLS employment report and elsewhere, documented by many analysts, support the observation that the economic contraction is hitting lower-income workers worse than others, and I point to two simple such measurements from the employment report. Strikingly, the drop in April in wages of production and nonsupervisory employees (a drop of 10.4 percent year-over-year) was greater than the drop in wages of total private sector employees (a drop of 8.4 percent, see chart below). That difference of 2 percentage points is by far the largest for any month since the two measures have been jointly produced starting in 2006. (Only data since 2018 are shown in the chart, but the very close relationship between the two measures is much the same back through the Great Recession.) Production and nonsupervisory workers generally earn less than total private sector workers, roughly 20 percent less overall. Until 2006, the production and nonsupervisory workers was the broadest category that BLS estimated–now they track both measures. Production and nonsupervisory workers account for about four-fifths of all nonfarm private sector employment, while total private sector workers cover all such employment, according to BLS, so that large overlap explains why wages for production and nonsupervisory employees would track closely with wages for total private sector employees. The wedge in growth in April is telling. Nonetheless, all sorts of wage data collection issues in April, which BLS has documented, make us cautious in over-relying on the precision of the data.

And continuing with the thought, withholding could be dropping less than BLS-measured wages because of the bigger drop in wages of lower-wage workers. The effective rate of withholding taxes from wages–that is, the amount of withholding as a percent of wages–is lower for lower-wage workers. Indeed, at low enough wage rates, many workers pay only payroll taxes and can be exempt from withholding for income taxes. In the Great Recession, the economic pain was spread more evenly around the workforce, and withholding growth fell more than wage growth as measured by BLS, not less as we saw in April (again, see chart at top). There could certainly be other reasons for withholding dropping less than BLS-measured wages in April, but wage disparities could be one clear factor.