Posted on May 4, 2020

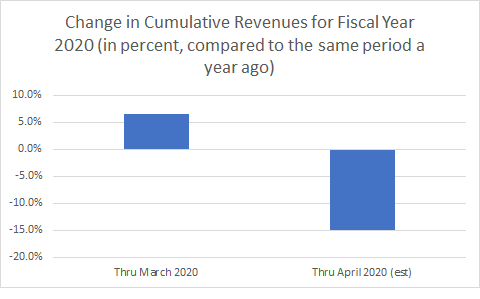

- We estimate that total federal tax receipts in April were down by 70 percent to 85 percent compared to amounts in April 2019, a drop so large that it would shift receipts for the current fiscal year (which started in October) from a gain of 6 percent through March to a decline of 13 percent to 18 percent through April.

- The decline in receipts in April is overstated because much was from IRS-granted payment delays that will reverse in the future, or from largely one-time legislative relief, especially individual tax rebates.

- Nonetheless, additional one-time factors during the remainder of the fiscal year, in particular substantial business tax refunds authorized by recent legislation and additional rebate payments, in conjunction with weak overall economic activity, will likely keep revenues down substantially for the year as a whole, even with no additional legislative or administrative actions.

I’ve promised to track federal tax receipts, so it’s time to come to grips with the results for April. Normally April is the biggest month of the year for receipts (for example, accounting for about 15 percent of receipts for each of the past two fiscal years), but it looks like receipts in April of this fiscal year will be the lowest month for the year to date. The Treasury Department will release the official results next week, but my estimate based on the Daily Treasury Statements is that receipts, on net, will be way, way down from April of last year, by somewhere in the range of 70 percent to 85 percent. That is down so much that receipts for the fiscal year, which had been higher by 6 percent for the first half of the fiscal year through March (compared to the same period a year ago), should now be down through April by, I’m estimating, somewhere between 13 percent and 18 percent (call it roughly 15 percent, see chart below).

The decline in receipts in April is overstated, in the respect that it wouldn’t normally be expected to continue, because much was from timing shifts or largely one-time factors. The main timing shift results from the IRS allowing individual taxpayers to delay filing their tax returns for 2019 and paying amounts due until mid-July, and the agency has also allowed both individuals and corporations to delay until July their quarterly estimated payments, also normally due in April (and again in June). Corporations can also hold off making their final payment in April for tax year 2019, which would otherwise be due then for most corporations. Although those actions hold down revenues in April, the amounts will be remitted later in the year, mainly in July if the current payment delays remain unchanged.

Some of the substantial decline in revenues in April, largely a one-time effect, resulted from the provision of the CARES Act (enacted in late March) that provides individual tax rebates, of which disbursements in April were almost $200 billion (out of a total of almost $300 billion expected after all are disbursed). According to estimates of the Joint Committee on Taxation and the Congressional Budget Office, roughly half of the rebate amounts should be classified as federal spending (not revenue reductions) in the official budget tabulations, because the rebate amount will exceed many taxpayers’ tax liability. Because we are measuring the change in tax receipts alone, the uncertainty of the Treasury Department’s estimate of that federal spending share is the main reason for my range of possible outcomes for total receipts for the month. The Congressional Budget Office, in its Monthly Budget Review for April that is scheduled to be released on Thursday of this week, should have a much better, more precise estimate of revenues in April than I have here–along with very useful analysis.

As a result of those legislative and administrative actions, revenues in April came mostly from withholding from paychecks of income and payroll taxes, and that source of revenue has been depressed with the cutback in economic activity. It looks like those withholding receipts will be down by roughly 15 percent this April compared to last April, though closer to 9 percent after removing the effects of this year’s calendar (primarily one fewer Monday, the biggest day) compared to the calendar from last year. A few percentage points of that 9 percent decline, we estimate, are due to delays in remitting payroll taxes allowed by the CARES Act, but even removing that effect, withholding was down by about 5 percent. (See previous post from a few days ago). That decline clearly reflects the effect of the economic downturn.

Although the various payment delays for April will largely reverse come July, and the rebates will have smaller effects going forward, I expect that additional one-time factors during the remainder of the fiscal year and weak overall economic activity will likely keep revenues down substantially for the year as a whole, even with no additional legislative or administrative actions. In coming months, corporate and noncorporate businesses should start getting substantial refunds of previous taxes paid, as allowed by the CARES Act, and that is expected to hold down revenue growth substantially. The Joint Committee on Taxation estimated that those refunds, which result from two main law changes, will total more than $150 billion in fiscal year 2020, and it doesn’t appear that much if any of that has been paid out by the IRS yet. In addition, upwards of another $100 billion in individual rebates still need to be disbursed, although again perhaps half of that will be considered federal spending instead of revenue reductions. Those combined amounts of about $200 billion in future revenue reductions could offset much of the amounts that individuals normally pay when they file their tax returns in April but that have been delayed until this July. And, depending on how the economy does in coming months, remittances of withholding taxes, which account for roughly two-thirds of gross tax payments in most years, could well remain down substantially through the end of the fiscal year.