Posted on October 7, 2022

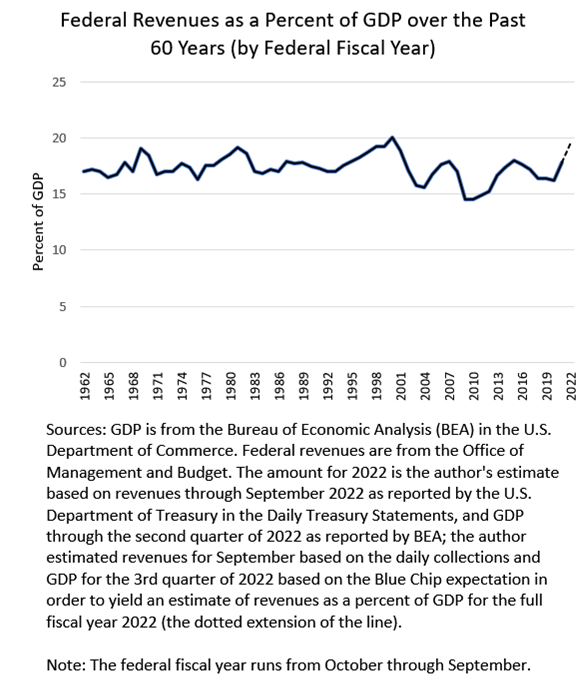

The 2022 federal fiscal year ended a week ago, and it is very clear that revenues boomed in the fiscal year, to just about $4.9 trillion we estimate, or about a 21 percent increase over the 2021 amounts. Revenues rose to an estimated 19.6 percent of the size of the economy as measured by gross domestic product (GDP); revenues relative to GDP have only exceeded that amount once in the past 60 years, in 2000 at the end of the dot-com bubble (see chart below). The only other times revenues were a larger share of GDP were in 1944 and 1945, for you history buffs. The fiscal year 2022 revenue amounts are not yet official: the Congressional Budget Office will release a better estimate of September revenues, and thus revenues for the full fiscal year, presumably next week in its Monthly Budget Review, and the Treasury Department will provide the official amounts for 2022 in its Monthly Treasury Statement as soon as late next week.

The 2022 revenue story is basically the same as we posted about a month ago. Relative to our expectation of a month ago, estimated payments of corporate and individual income taxes in September were a bit higher, and tax withholding amounts from paychecks were a bit lower as withholding growth has continued to weaken in recent months (see previous post on withholding). On net, revenues were higher than we had expected a month ago by some $15 billion or so, but GDP in the interim was revised up historically by the Bureau of Economic Analysis for 2020 onward. Overall, including our estimate of GDP for the third quarter of 2022 that is based on the Blue Chip consensus, we estimate that revenues as a share of GDP in 2022 were just a little below what we expected a month ago.

Much of the strength in revenues in fiscal year 2022 presumably reflects strong economic activity, along with large stock market gains, in 2021, plus some effects from tax law changes (including the payment of some payroll taxes that were allowed to be deferred from 2020 during the worst of the pandemic). Full tax return information is not yet available for 2021, but partial data from individual income tax returns shows very large increases in capital gains and business incomes. Those types of income go disproportionately to higher-income taxpayers, who face the highest tax rates. (Note that the partial data from the IRS include only information from tax returns processed through mid-July of this year, and last year, and thus notably leave out many higher-income individuals who file for an extension until October). Much of the resulting increase in tax liability gets reflected in the following federal fiscal year when taxpayers file their tax returns for that year. And we should note that capital gains realizations–gains recognized for tax purposes when the appreciated asset is sold–generate significant amounts of federal revenues, but GDP doesn’t include the capital gains income because that income largely reflects gains in asset prices from past years, not from the year in which the gains are realized. Thus, the ups and downs of capital gains realizations–and they move way up and way down over time–move revenues as a share of GDP significantly.

For the new 2023 fiscal year, we should certainly expect revenue growth to fall from its high growth rate of fiscal year 2022, and revenues to fall from the lofty percentage of GDP that was reached. The economy is clearly slowing, and tax withholding growth has slowed along with it, and likely business income growth is slowing as well. And the decline of the stock market in the 2022 calendar year-to-date should cause capital gains from stock sales to decline for the year; the corresponding effect on federal revenues typically gets reflected in an outright decline, sometimes a very significant decline, in tax payments with filings of individual income tax returns in the next tax filing season.