Posted on May 26, 2020

Summary

- Now that we have estimates of 2019 wage growth from the BLS Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages, we can estimate that the 2019 average wage index used for Social Security purposes will grow in the vicinity of 3.5 percent for the year. The Social Security Administration should release the official amounts in October.

- The average wage index affects Social Security benefits, the maximum amount of wages subject to Social Security taxes, and other parameters of the Social Security system.

- The 2020 average wage index could fall sharply as a result of the pandemic. Due to a quirk in the calculation of Social Security benefits, that fall could have significantly negative effects on future Social Security benefits for individuals who turn 60 this year.

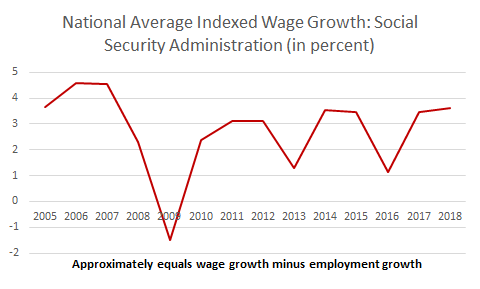

There are a number of different measures of overall wage and salary growth that serve different purposes. Last week we posted how wage data from the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages for the fourth quarter of 2019, released by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), now allows us to estimate closely how wages will grow in 2019 in the National Income and Product Accounts, a very useful measure for macroeconomic forecasters. That BLS measure of wages also tells us what we can expect for the 2019 Average Wage Index (AWI) calculated by the Social Security Administration (SSA), which is used for a variety of purposes, including the calculation of Social Security benefits. SSA releases the AWI for the prior year every October. We expect that the AWI for 2019 will grow in the vicinity of 3.5 percent, little if at all different from the 3.6 percent recorded in 2018 (see chart below). Overall wage and salary income in 2020, and therefore the eventual calculation of the AWI, is clearly looking quite poor, obviously measuring the immediate hardship for many workers during the pandemic. A likely sharp decline in the AWI will have implications for Social Security benefits and the maximum amount of wages subject to Social Security tax. Because of a bit of a quirk in the Social Security benefit calculation, individuals turning 60 in 2020 look to have their future benefits cut, possibly significantly.

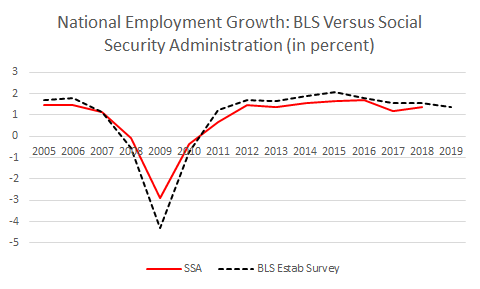

The average wage index is measured, in effect, as total wages in the economy divided by total employees, calculated by SSA from tax return information (W-2s filed by employers). Growth in the AWI series, therefore, is roughly the growth in economywide wages minus the growth in the total number of employees. SSA will probably announce the AWI measure for 2019 in October of this year. However, that first part of the AIW growth calculation for 2019, growth in total wages, should be very close to the growth in BLS-measured wages in 2019, which we now know (see chart below). Although the BLS-measured wages are from administrative data compiled for purposes of the unemployment insurance system, rather than the tax return (W-2) data used for the SSA measure of wage growth, the two measures have yielded nearly the same growth rate historically (again, see chart below). So, we should expect something in the vicinity of 4.7 percent for 2019 national (economywide) wage growth.

The other part of the AWI calculation for 2019, the growth rate of employment, is not quite as predictable with current information as are total wages, but almost so. The measure of employment from the monthly BLS establishment employment survey lines up pretty closely with the SSA measure of the number of workers (see chart below). So, we should expect something in the range of 1.1 percent to 1.2 percent growth for 2019 when SSA releases the AWI information this autumn. Subtracting that amount from the 4.7 percent wage growth expected for 2019 yields the expectation for growth in the vicinity of 3.5 percent in the average wage index for the year. That compares to 3.1 percent in the intermediate assumptions published by the Social Security Trustees in their annual report released last month.

Although growth in the AWI for 2019 is expected to be much like that in 2018, we won’t be able to say the same for the 2020 AWI. In recessions total wages tend to drop more than total employment. That is because anyone working at all during the year is counted as employed for the AWI measure. Even if a worker’s average hourly earnings didn’t change, a worker unemployed for part of the year could work many fewer hours and earn much less overall income, and that is the relevant measure for the AWI. Depending on how quickly the economy recovers, we can expect the AWI to drop markedly in 2020, possibly multiple times as much as the 1.5 percent drop in 2009 during the financial crisis.

Now what about those individuals who turn age 60 during 2020? Unfortunately, they could see a significant, permanent cut in their future Social Security benefits as a result of the pandemic. I went online to check my math that it affects people turning 60 this year (it does), and I found one paper, written by Andrew G. Biggs of the American Enterprise Institute, that already lays out the problem very well. Although my guess at this point would not have average wages dropping nearly as much as the 15 percent he uses for illustrative purposes, average wages are likely to fall sharply. The benefit problem is that the Social Security benefit calculation for a worker, which takes a worker’s entire work history into account, begins by inflating wages earned in each year of the worker’s life by the growth in the AWI between that work year and the year the worker turns 60. In that way, the worker’s wages each year get indexed to wage growth in the economy. If average wages are depressed in the year the worker turns 60, that means each year’s wages that the worker earned are inflated to a smaller amount than if the AWI didn’t fall in that age 60 year. And for a worker who has turned 60, it doesn’t matter for purposes of the Social Security benefit calculation what happens to the AWI in any following year. So, even if the economy were to rebound completely in 2021, that wouldn’t affect that calculation of the Social Security benefit for workers who turned 60 in 2020. If the Social Security benefit calculation instead used something more of a moving average, such as indexing a worker’s lifetime earnings to the average of the AWI over ages 58 to 60 and allowing for an inflation adjustment alone for the age 60 year, then any one year’s AWI would have much less impact.

Andrew Biggs estimates that a 15 percent drop in the average wage index in 2020 would permanently reduce future Social Security benefits for a 1960-born middle-income worker by about 13 percent. Effects on other workers born in 1960 would be similar. Again, I don’t expect the drop in the AWI to be that large, but there could still be a very sharp drop. And a drop in the AWI for 2020 would have other effects, such as stopping any increase in the maximum amount of wages subject to Social Security taxation in 2022.

We won’t need to wait until October 2021, when SSA should announce the 2020 AWI, to estimate pretty closely how much the AWI will fall in 2020. We’ll get information along the way on wage and employment growth, and indeed we should be able to get a reasonably close estimate by this time next year.