Posted on October 4, 2021

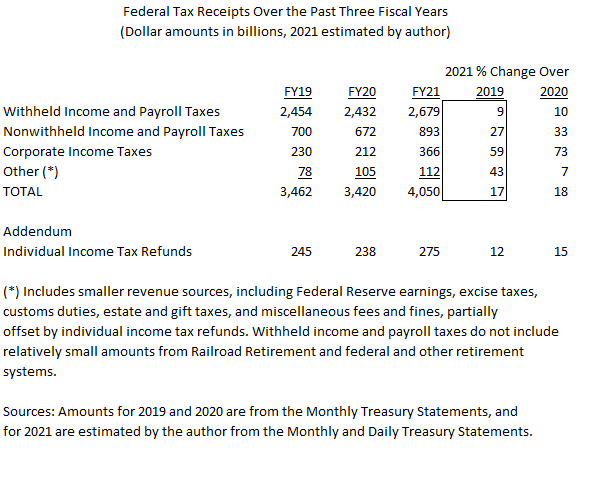

The end of the federal fiscal year (on September 30) is always a good time to take stock of receipts for the year and what they tell us about the economy. This post will sort of bring together our different posts over time about different revenue sources. In short, federal revenues have been doing quite well, surprisingly so, at least if you had asked me a year ago. Although we’ll get more precise tabulations from the Congressional Budget Office and the Treasury Department over the next week or two, we estimate that total federal revenues reached roughly $4.05 trillion in fiscal year 2021, an increase of 18 percent over the 2020 amount and a similar 17 percent over the 2019 amount (see table below). Both are large increases, but I prefer to focus on 2021 relative to 2019, back to before the pandemic; revenues tend to fall most in the year after a recession begins, when taxpayers file their tax returns for the recession year and typically make much smaller payments than usual or get much bigger refunds. Comparing 2021 to 2019 thus compares the year with typically the most serious hit to federal revenues with the year before the recession began. That comparison also removes a lot of effects on revenues from enacted law changes that were concentrated in 2020 and had much smaller effects in 2021, and clearly none in 2019. So, revenues in 2021 were 17 percent higher than in 2019, quite a strong two-year increase in revenues–we haven’t seen two-year growth in total revenues that high since 2015. And why would it happen now, given all the economic problems that have gone along with the pandemic?

The answer will take more time and information to really assess because of the lags in taxpayers filing their tax returns for the year and the data becoming available from the IRS , but we believe the answer is a combination of a powerful response from policymakers as well as an uneven recession and recovery in which higher-income taxpayers have fared much better than others. First, perhaps the easier part of the story, namely the policy response: Since the pandemic began, federal policymakers have passed several major pieces of legislation that pumped a large amount of financial resources to individuals and businesses, what is generally called fiscal stimulus. And we add to that the actions of the Federal Reserve, which has bought a huge amount of Treasury securities and mortgage-backed securities, and also lowered interest rates under the Fed’s control to about as low as they can go. Although a good amount of the funds from legislation have been targeted to individuals and businesses most in need, another chunk has gone to people not in so much need or none. The Fed’s injection of funds has supported the overall financial markets, which helps everyone to some extent, but the effects are hard if not impossible to target well to those individuals most in need. A case in point is booming asset prices, especially stocks and housing, which we believe have benefited from the Fed’s actions and largely accrue to higher-income households.

That brings us to the second point, the uneven nature of the recession and recovery. We think we see the effects of higher-income individuals doing better than others when we assess revenues from all the major tax sources. In particular, individual Income tax revenues, the largest federal revenue source, have been doing quite well, and they are largely paid by higher-income taxpayers: in 2018, the last year for which we have the information from the IRS, about 83 percent of the individual income tax was paid by taxpayers with more than $100,000 in adjusted gross income. Therefore, it should not be a surprise that strong growth in income tax revenues corresponds with strong income growth of higher-income taxpayers.

Look at how the major federal revenue sources did in 2021 relative to 2019:

- Nonwithheld income taxes have risen by about 27 percent over the past two years. That includes strong payments with tax returns back in May, which stemmed from 2020 economic activity (see previous post) and quarterly estimated payments that have risen by similarly strong percentages in recent quarters (see post about the September quarterly payment). These amounts typically stem from nonwage incomes of higher-income taxpayers, such as capital gain realizations and business incomes (from partnerships, sole proprietorships, and other pass-through entities). The stock market has continued to boom through the recession and recovery after an early drop, and trading volumes were very high last year, combining to presumably boost capital gains realizations, rather than experience big drops such as those recorded during the past two recessions. Of quarterly estimated payments in tax year 2018, about 95 percent were paid by taxpayers with incomes in excess of $100,000, and just under 90 percent of final payments with tax returns (paid during 2019) were made by that same group.

- Amounts of income and payroll taxes withheld from paychecks (often referred to as “withholding”) have grown by about 9 percent, we estimate, over the past two years. That amount would be larger, more like 11 percent, we estimate, if not for tax cuts affecting withholding enacted since the pandemic began. Withholding has also been growing even faster in recent months, we estimate, more like 13 percent to 14 percent or higher compared to the same months two years ago (again, removing the estimated effects of tax law changes). But even at 11 percent two-year growth, that’s an average of 5.5 percent per year, which would be about normal growth in withholding per year. Withholding has been growing a lot faster than wages as reported in the National Income and Product Accounts, which indicates that average tax rates are rising because more wage growth has been accruing to higher-income taxpayers, who face higher income tax rates (see recent post). That effect would be muted somewhat because almost half of withholding stems from payroll taxes, which are not as disproportionately paid by higher-income taxpayers as are income taxes because the Social Security payroll taxes are limited, being assessed on the first $142,800 of wages per employee this year, and are assessed at a flat tax rate. (We cannot distinguish payroll tax payments from income tax payments in real time.)

- Corporate income taxes have been booming, up about 60 percent compared to amounts two years ago, indicating large increases in taxable corporate profits. Higher-income taxpayers disproportionately benefit from higher corporate profits through dividends and capital gains. Corporate income tax payments in 2021 were even well above amounts in 2016 and 2017, before corporate income tax rates were reduced substantially by policymakers. We attribute the big profit and corporate tax revenue increase in 2021 to several factors including commodity price inflation in recent months that very directly benefits certain corporations; government policies enacted since the pandemic began that have, to some extent, boosted the corporate bottom line; and a change in the mix of corporate profits between profitable firms, which face income taxes, and unprofitable firms, which don’t (see previous post). That last factor doesn’t affect overall profits, but does raise tax payments for a given dollar of overall profits. A wild card here is that provisions of past legislation could have increased corporate refunds that haven’t been disbursed yet; many of those refunds require filing by paper that could require hand processing by the IRS that has been well delayed by the pandemic. Those refunds could be delayed until fiscal year 2022 and reduce net corporate tax payments then.

So, fiscal year 2021 was a very unusual year for federal revenues, booming in the year after a recession. Normally in recessions, as noted earlier, revenues fall sharply in the second year–such as the big drop in revenues in 2009 and 2002. But in those recessions the downturn had more broad based effects across individuals in different demographic, occupational, and income groups. Capital gains and other incomes largely affecting higher-income taxpayers were hit along with incomes of other taxpayers. We infer from recent tax payments that such is far from the case in both 2020 and 2021–with higher-income taxpayers faring much better than other taxpayers.