Posted on November 3, 2021

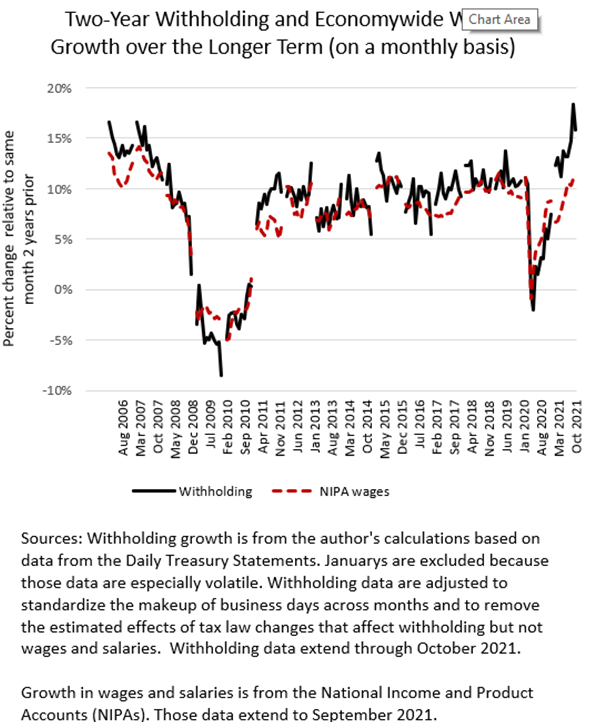

First, we measure that economywide income and payroll taxes withheld from workers’ paychecks and remitted to the U.S. Treasury (so-called tax withholding) was strong in October, increasing by an estimated 15.8 percent compared to the amount from the same month two years ago, before the pandemic (see solid line in the chart below). It now seems clear, as we had suspected, that the very strong 18.4 percent growth measured in September was a measurement anomaly due at least in part to a shift in the timing of the Labor Day holiday. Regardless of the pullback from the September growth, withholding growth in October was higher than that from August (14.7 percent) and even more so than in each month from May through July (13-14 percent). Because tax withholding is based largely on the amount of wages and salaries paid to workers, we interpret the data as meaning that economywide wages and salaries are continuing to improve following last year’s recession.

Second, we estimate that economywide tax withholding is growing much faster than overall wages and salaries as measured in the National Income and Product Accounts (again see the chart below). When overall tax revenues from withholding are growing faster than wages and salaries, that means that average tax rates are rising, which is a sign that wages of higher-income taxpayers, who face higher tax rates, have been growing faster through the recession and recovery than have the overall wages of moderate- and lower-income taxpayers. Tax withholding tends to grow faster than wages and salaries in a growing economy by modest amounts, but the increase recently has been well outpacing that normal tendency (see second chart for a longer-term perspective). That is very consistent with other data that show higher-income individuals faring much better in the recession and recovery than have others. Withholding growth well outstripping wage growth could also mean that wages are being underestimated in the National Income and Product Accounts and will be revised up in future reports, but other data sources, such as those measuring recent changes in employment by income group, suggest that the wage distribution effects could well be large enough to explain the unusually high deviation between tax withholding and wage growth.

Note that we adjust the reported withholding amounts to remove the estimated effects of tax law changes (which we estimate are small over the recent two-year periods) and to standardize the number and make-up of business days across months. We look at two-year growth because one-year growth rates are currently unusually high, being measured relative to depressed levels from a year ago, making them difficult to interpret, and because the one-year growth rates are more susceptible to error measuring the tax law change effects, which were unusually large last year.