Posted on January 18, 2022

Summary

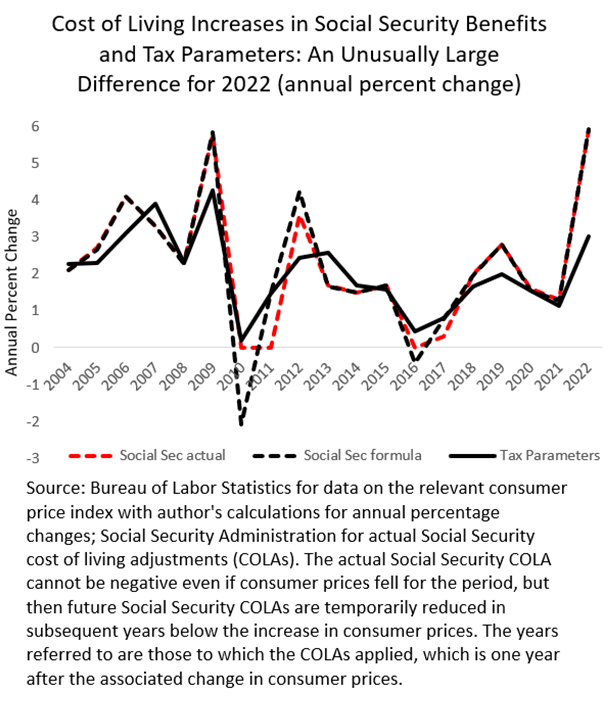

- Social Security benefits and many tax parameters (such as the tax brackets and standard deduction) are indexed to inflation by law. As a result, effective January 1, 2022, Social Security benefits for a beneficiary rose by 5.9 percent, and the indexed tax parameters by only about 3.1 percent. Different indexing formulas are applied to Social Security benefits and the tax parameters, but normally they move much more in sync, and over the long term have averaged very similar increases.

- That difference for 2022 should reverse when inflation moves back down again, at which point Social Security benefits should grow more slowly than the tax parameters.

- The timing of the ups and downs of inflation affect individuals and the overall economy through the indexing formulas. The effect mainly results because Social Security benefits and the indexed tax parameters are by necessity adjusted with a lag following past inflation.

- When inflationary pressures are reduced–perhaps as a result of the Federal Reserve raising interest rates or from the supply of goods and services catching up with demand in the economy–then we should likely see some support for the economy coming especially from the indexed tax parameters. That support would be the flip side of some fiscal restraint that occurred in 2021, when inflation increased without an immediate increase in the tax parameters or Social Security benefits.

Inflation indexing of the major tax parameters, such as the tax brackets and the standard deduction, doesn’t garner a lot of excitement, but the cost of living adjustments (COLAs) for Social Security benefits sure do. Usually the indexing for inflation of the tax parameters and Social Security benefits move pretty closely together, with both being calculated based on measures of consumer price inflation for the previous year. But differences in the exact indexing formulas specified by law and applied for the two purposes have caused a beneficiary’s Social Security benefits in 2022 to go up by much more (5.9 percent) than the indexed tax parameters (about 3.1 percent) [see chart below]. That difference was caused by the interaction of the exact formulas in law and how prices started jumping partway through 2021. Such differences typically get reversed in following years when inflation reverts.

The economy is affected by the way the indexing formulas are constructed and the lags before the indexing takes effect. The indexing of many of the tax parameters to inflation avoids the problem that inflation, including wage gains that keep up with the overall price increases, would otherwise push more income into higher tax brackets and also erode the value of the standard deduction, both of which would in turn cause increases in average tax rates without any action by policymakers. Similarly, indexing Social Security payments for inflation keeps inflation from eroding the amount of goods and services that a Social Security beneficiary can purchase. In those ways, indexing tax parameters and Social Security payments for inflation largely keeps inflation from contributing to fiscal restraint (that is, the opposite of fiscal stimulus from federal spending and tax cuts that boost the economy, at least in the short run). The timing of the ups and downs of inflation, however, is critical. If the Federal Reserve increases interest rates this year in order to reduce the current amount of inflation, likely weakening economic growth, that would cause both the Social Security COLAs and tax indexation increases to fall, with the Social Security COLAs falling by more, but critically with a lag. More details on the indexing formulas and the timing of the fiscal stimulus effects follow. It gets very detailed, so you could stop here and just note that at some point the Social Security COLA will move back below that of the rate of indexing of the tax parameters. Or you could continue below….

Alright, you’re still with me. The different formulas for indexing Social Security benefits and the tax parameters have advantages and disadvantages, but having two such formulas certainly is confusing. Social Security benefits, starting on January 1 of each year, go up by the percentage increase in the consumer price index for urban wage earners (the so-called CPI-W) measured for the July to September quarter for the prior year relative to the July to September quarter for the year before that. So, only 3 months in a year are relevant for the calculation, and if consumer prices jump in the July to September quarter, then the Social Security COLA jumps starting in January of the next year. Large gasoline price increases in some summer months, typically very temporary, have caused that effect in history. The tax parameters, on the other hand, go up by the percentage change in the consumer price index for all urban consumers (CPI-U) measured for the full September to August period of the prior year compared to the September to August period in the year before that. (The August CPI is available from the Bureau of Labor Statistics in mid-September, allowing sufficient time, a few months, for the IRS to calculate the indexed tax parameters and incorporate them into tax tables and tax forms, etc. by the beginning of the next calendar (that is, tax) year.) So, importantly, for the tax parameters, it is the average of 12 months that matters. One important technicality is that, starting in 2018, the tax parameters have been indexed by the chained CPI-U, which tends to increase by about 0.2 percentage points slower than the regular CPI-U, thus raising revenues. Another technicality is that Social Security payments cannot decrease if there is deflation, and the actual CPI-W formula would have caused such negative Social Security COLAs in 2010 and 2016, which were zeroed out instead (again, see the chart for the distinction between what the formula would yield including negative Social Security COLAs and what the actual COLA was including those zeroed out and subsequent years). Following the zeroed out years, the subsequent COLAs were then reduced until the overall COLA over a period of years lined up with overall price increases.

As a result of the 3-month average used for Social Security benefit indexing and the 12-month average used for tax parameter indexing, Social Security benefit indexing is more volatile than tax indexing. That can be observed pretty clearly for the past two decades in the chart above, and the standard deviation of the Social Security COLA is almost twice that of the tax indexing increases. Typically Social Security benefit percentage increases have moved above and below tax indexing percentage increases not because of the difference between the CPI-W and CPI-U (or the chained CPI-U), which move pretty closely in lockstep (the chained CPI-U slightly less so), but rather because of the limited 3-month period assessed for Social Security indexing. When assessed over a long period of time, Social Security benefit COLAs and tax parameter percentage increases have averaged out to about the same amount–although in the future that 0.2 percentage point difference from the chained CPI-U should cause a small permanent difference, at least unless (or until) Social Security benefits are indexed to the chained measure of consumer prices as well, as many analysts have proposed.

Although the Social Security indexing formula yields more volatile results, it does respond faster to permanent changes in inflation, which could be a limited advantage. For example, if inflation remains in the range of 6 percent to 7 percent, then the tax parameters will get indexed to that rate of increase, but not as quickly as Social Security benefits.

But normally inflation changes are temporary, and the Social Security and tax parameter changes tend to balance out, so when can we expect the Social Security COLA to drop below the tax parameter indexing increases, and what are the implications for fiscal stimulus or the opposite, fiscal restraint? Well, that requires me to be able to predict future inflation, and that is a rather tall order, and the precise timing is critical. I can though say what happens under different scenarios. If both the CPI-W and chained CPI-U increased at annual rates of just 2 percent starting immediately this month and going through 2024 (a clearly highly unlikely rapid slowing in inflation), the Social Security benefit COLA in 2023 would be 3.4 percent, while the tax parameters would rise by 5.2 percent–near a complete reversal of the 2022 experience (see table at the bottom).

In that unlikely example of a rapid taming of inflation–perhaps from a worsening of the pandemic that could lower aggregate demand, or from very quick effects from the Federal Reserve raising interest rates–the tax parameter increase in particular in 2023 would partially offset the economic weakness. The Social Security and tax indexation formulas and the lagged implementation would bring about some fiscal stimulus in 2023, the flip side of fiscal restraint that occurred in 2021 when inflation increased without an immediate increase in tax parameters or Social Security benefits. The future effect would be even stronger if prices immediately stopped growing altogether, really just an illustrative scenario rather than one with any likelihood of happening: then the Social Security COLA in 2023 would be just 2.1 percent and tax indexation would be 4.6 percent. With zero inflation and a likely overall economic contraction, the tax indexing and Social Security COLAs would help support the economy in 2023 (along with a bunch of other so-called automatic stabilizers). They would help support the economy in 2022 as well, because the already-set COLA and tax parameter increases would well exceed the actual inflation rate.

In both of those immediately-lower inflation cases, the tax indexing formula still brings about a substantial amount of indexing in 2023 in part because we already have recorded 4 of the 12 months of inflation (September through December 2021) that determine a full year’s amount of inflation for the 2022 inflation calculation; the Social Security COLA, on the other hand, has not yet had any of the 2022 values necessary for the calculation. And the prior year’s upward movement in consumer prices (even before September 2021) also carry through for some period of time when calculating annual average increases.

Also note that if inflation doesn’t revert much at all, measuring, say, 6 percent going forward through 2024, then the Social Security COLA and inflation indexing increases would be about the same in 2023 and 2024 at 6 percent. In that case, the indexing of the tax parameters in 2022 (3.1 percent) would be well short of the inflation rate, and the delayed effect of the indexing formula would cause some fiscal restraint this year by raising average tax rates. It isn’t until the inflation measure reverts that we’ll get the fiscal support from the indexation formulas and delayed implementation, and at that point the Social Security increase falls short of the tax indexation increase.

It seems that the more likely outcome is somewhere in the middle, with the Federal Reserve gradually raising interest rates, bringing about slower economic growth and inflation, and with the supply of goods gradually catching up with demand and lowering inflation through that channel. In that scenario, the tax parameters and Social Security COLAs temporarily help to support the economy and offset some of the slower economic growth–until the inflation rate stabilizes at some lower level.

Maybe this all just punctuates why inflation indexing of the tax parameters is not an exciting subject. But it and Social Security benefit indexing certainly have important effects on individuals and the overall economy.