Posted on March 25, 2021

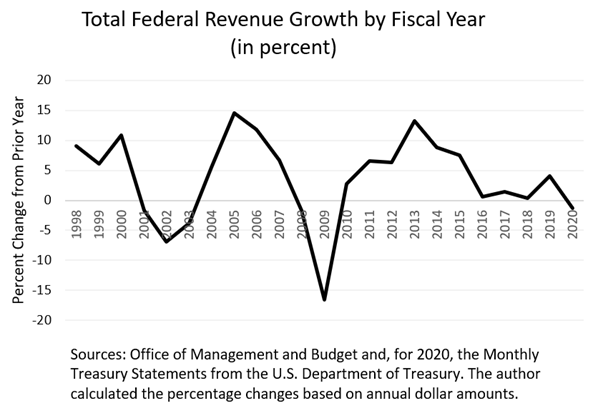

I learned as a federal revenue estimator never to underestimate the effects of a recession on the following year’s receipts, when individuals’ final payments in April would drop sharply and refunds through the tax filing season would increase significantly. I learned those lessons in April of 2002 and 2009, well after the associated recessions started in March 2001 and December 2007, respectively (see chart below). Total federal revenues in 2002 dropped by about 7 percent and in 2009 by almost 17 percent. Revenues in fiscal year 2020 dropped by about 1 percent, with revenues in the first half of the fiscal year up by about 6 percent (compared to the same period in fiscal year 2019), and then down by about 7 percent in the second half of the fiscal year from April to September after the pandemic and accompanying public health responses brought about the sharp economic contraction. The responses also included federal spending increases and tax cuts to provide relief to individuals and support to the overall economy. So, revenues didn’t fall very much for the full 2020 fiscal year, but should we expect a significant decline in fiscal year 2021, like we saw in 2002 and especially in 2009?

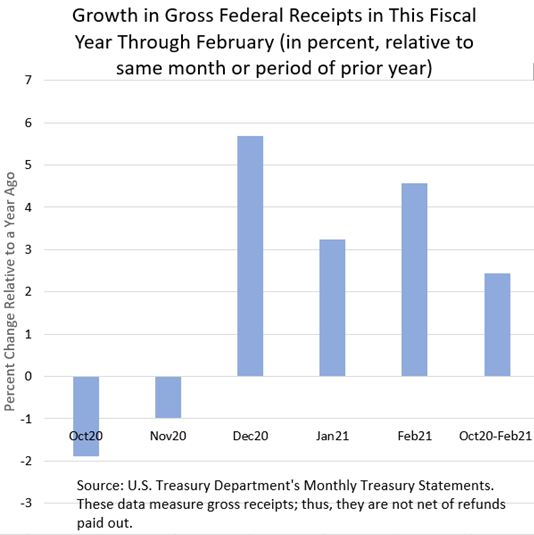

Maybe I haven’t learned the lesson fully, but this time feels very different. Total receipts in the first five months of fiscal year 2021 overall have grown, and increasingly so month by month (see chart below). Because of the late start to the 2021 tax filing season (for tax year 2020), refunds are well behind last year’s pace, and that distorts the measure of growth in net receipts, so I will focus only on gross receipts from all sources–thus not reduced by refunds. Gross receipts were up by 2.4 percent for the first five months of the fiscal year (from October 2020 through February 2021) compared to the same period in the prior year. And by February gross receipts were 4.5 percent higher. They are up by about 10 percent in the first three plus weeks in March, and the year-over-year comparisons will only become easier in coming months when this year’s receipts are compared to the depressed levels of a year ago, and as the economy presumably continues to recover. Employer remittances of withholding for income and payroll taxes of their employees, which usually account for about two-thirds of gross receipts from all tax sources, are set for big year-over-year increases in coming months barring something very unexpected: I would expect to start seeing year-over-year percentage growth rates in withholding at least in the teens, probably higher, starting in April and running for multiple months. That expected rapid growth in withholding is reinforced by my estimate that, barring enactment of further Congressional legislation, the tax cuts to withholding in the second half of fiscal year 2020 were bigger than those for the second half of 2021. Those factors seem to point to a significant boost in overall federal revenue in the second half of this fiscal year compared to the second half of fiscal year 2020.

But only time will tell how final payments and refunds from tax year 2020 will affect this year’s tax receipts. Normally in the year after a recession begins, final payments drop sharply as higher-income taxpayers experience drops in business income, capital gains realizations, and dividends. Lower- and middle-income workers who become unemployed during the year often get bigger tax refunds than normal; that occurs in part because while they were employed, they were withheld at an income tax rate that ended up being too high, calculated under the assumption that the person would be working the full year.

There are lots of questions about how final payments and refunds will turn out given the unexpected bounce back in wages in the second half of calendar year 2020 and with the stock market rebounding so quickly to new highs. There are lots of confounding factors at play in 2020. Given the delay in the deadline for filing income tax returns until mid-May, and how it takes the IRS some time to process the returns and count the money, we won’t know the results of final payments and refunds for some time. There is still about half of the fiscal year to go, but it sure looks like it would take a very big drop in final payments and increase in refunds this tax filing season to push overall revenue growth negative for the full year. Indeed, it’s hard for me to see how net revenues under current law don’t end up fiscal year 2021 growing above, and maybe considerably above, the 2.4 percent rate we’ve seen for gross receipts through February. But I keep learning new lessons, or having old ones reinforced.