Posted on August 18, 2020

Summary

- The Joint Committee on Taxation estimated that two business provisions of the CARES Act allowing for retroactive use of losses would reduce revenues by a combined $155 billion in fiscal year 2020.

- The timing of the revenue effects from the provisions is rather complicated, but I’m skeptical that we’ll be seeing a very large amount of refunds from those two provisions before the end of the fiscal year in six weeks, both because some of the effects should be delayed given the processing timetable and the hampered IRS operations during the pandemic, and because some of the effects don’t work through refunds.

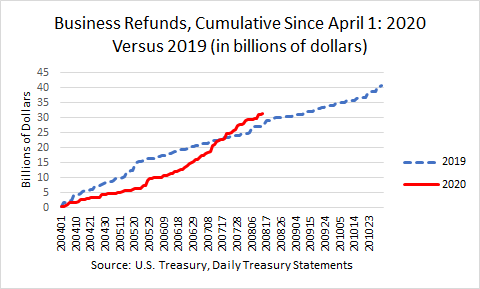

I’ll address the complicated issue of whether we should be seeing, or will shortly see, a big run-up in tax refunds as a result of two provisions of the CARES Act with retroactive components: allowing firms (mainly corporations) to carry back losses from 2018, 2019, and 2020 for up to five years to receive refunds of past taxes paid; and allowing individuals with substantial business losses (amounts more than $250,000 for a single taxpayer, or $500,000 for a joint filer, called “excess business losses”) in those same three years to once again immediately claim those losses against non-business income for tax purposes–they had been allowed to do that until tax law changes enacted in late 2017 allowed the excess losses to only be carried forward to future years. (Believe it or not, I’m simplifying in part because there are other limits on use of such losses by individuals that haven’t changed.) In short, I’m skeptical that we’ll be seeing a very large amount of refunds from those two provisions before the end of the fiscal year in six weeks, both because some of the effects should be delayed and because some of the effects don’t work through refunds. We certainly haven’t seen a big jump in refunds at this point (see chart above for total tax refunds paid mostly to corporations, relevant for the carryback provision).

The two provisions are worth a lot of money that should be apparent in tax collections if the Congressional estimates are accurate. The Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) estimated, at the time of enactment of the CARES Act in late March, that those two provisions would reduce federal revenues by about $155 billion in fiscal year 2020 (which ends on September 30), about evenly split, with slightly more from the carryback provisions ($80 billion) than from the excess business loss provisions ($74 billion). (The effects of the carryback provision get mostly offset with revenue increases in later years, when firms no longer deduct those losses. The excess business loss provision loses another estimated $64 billion in fiscal year 2021.)

There’s a lot going on with those provisions and how and when the revenue effects should occur. I don’t have any knowledge about the construction of the JCT revenue estimates, but I’m pretty sure those were very complicated estimates to make, given three tax years affected–each with a different profile on how and when the revenue effects would occur–and two separate provisions.

First, the carryback provision: to start at the beginning, firms with losses in 2018 can now carry back those losses to receive refunds of taxes paid back as far as 2013. They can either file amended tax returns for those years to obtain refunds, which is a slow process, or they can file for a so-called quick refund (often called a “quickie refund”, but officially called the more mundane “tentative refund”). Although normally it would be too late now to file for a quick refund for tax year 2018, for this year the IRS has allowed taxpayers (those majority of firms whose tax year matches the calendar year) to file as late as June 30; then the IRS tries to provide the refunds within 45 days, and otherwise is supposed to within 90 days, with interest. So, 45 days from June 30 is, well, just about now. And 90 days would just squeak into the end of the 2020 fiscal year. Have we seen a big run-up in corporate refunds yet? No. Since April 1, business refunds (mainly for corporations) are now running only about $3 billion (or about 12 percent) above (see chart at the top). How quickly the IRS will be able to get the refunds to businesses this year, given the pandemic’s effects on IRS operations, is a big question. And, as discussed below, the refunds for tax year 2018 should only be a part of the JCT’s overall estimate of revenue losses for fiscal year 2020.

Besides refunds of 2018 losses, some of the revenue losses will be from tax year 2019. If a firm’s losses in 2019 were so large that it can now carry them back, they will have to wait until they file their tax returns for the year before applying for a quick carryback refund. But those returns weren’t due until July 15 this year for calendar year filers and most large firms routinely ask for an extension until mid-October. And even 45 days from July 15 is skirting the end of the fiscal year, much less 90 days. It’s even possible that some firms will elect not to carry back 2019 losses, because they think the political winds may mean higher corporate income tax rates in the future, potentially making carryforward use of the losses in the future more valuable than carrying them back today–and they can even wait until after the election to decide.

And it’s hard to see much immediate effect from tax year 2020 losses, and certainly not from refunds. Firms with losses this year can only reduce their estimated payments to zero, with or without the law change; they’ll have to wait to get carryback refunds for prior years at least until after the tax year ends, when the amount of losses this year becomes known. One item of interest is that the law change could induce firms to accelerate their expenses into 2020 in order to carry the losses back, perhaps to a tax year before 2018 with a 35 percent corporate income tax rate, rather than the 21 percent rate in effect since 2018. That could induce some firms that would otherwise pay quarterly estimated taxes this year to perhaps pay none instead, and that effect could be in the JCT’s revenue estimate. However, gross corporate payments were only down by $25 billion, or 21 percent, from April through July 2020, compared to the same period last year. That’s not a lot given the economic downturn, especially if some portion of the decline was from the effects of the law change on quarterly estimated payments.

And there are no “quick refunds” allowed for individuals, such as those generally high-income individuals no longer subject to the excess business loss limitations for 2018 through 2020. They need to file an amended return for 2018, a process that doesn’t have the 45- or 90-day IRS processing timetable. And like with corporations, many such individuals probably haven’t even filed a tax return for 2019 yet; it’s a common practice for higher-income individuals with business income to file for an extension until mid-October. I certainly don’t see any evidence yet of a surge in refunds of individual income taxes. It’s hard for me to see how those estimated revenue losses from the excess business loss provision could occur so quickly, especially with how the pandemic has slowed the ability of the IRS to operate.