Posted October 18, 2020

Summary

- Federal revenues declined by 1 percent in the just-concluded 2020 fiscal year, and remained roughly stable as a share of GDP.

- Revenues typically fall sharply relative to GDP in recessions, and often with much of the effect hitting with a lag. Revenues remained stable relative to GDP in 2020 in part because of the lack of substantial legislative tax cuts, and it is unclear because of the nature of this recession if the revenue share of GDP will decline with a lag in fiscal year 2021.

- Revenues would have fallen substantially relative to GDP in 2020 if the tax rebate payments enacted in the CARES Act had been classified as revenue reductions, as with past such rebates, instead of spending as the Treasury Department classified the rebates this time.

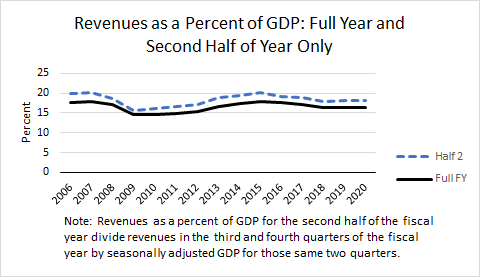

The Treasury Department two days ago released its tabulation of federal receipts for fiscal year 2020, which measured $3.42 trillion, 1.2 percent lower than in fiscal year 2019. Revenues look to have been about 16.3 percent of GDP for the third year in a row–based on our estimate from general expectations for GDP for the final quarter of the fiscal year, for which we get the first official data from the Commerce Department on October 29th. Looking just at the pandemic-affected second half of the 2020 fiscal year–so from April through September–revenues fell by about 7 percent compared to the same period in 2019, and, as with the full year, also remained relatively stable as a percent of GDP (see chart below). Revenues relative to GDP are typically larger in the second half of the fiscal year because of tax payments with filings of tax returns, while refunds with tax return filings are largest in February and March that occur in the first half of the fiscal year.

Typically in recessions revenues decline sharply as a share of GDP, but that hasn’t occurred so far in this recession. In part that is because revenues tend to lag somewhat in downturns: withheld income and payroll taxes drop immediately with the downturn in economic activity, but significant additional weakness hits when taxpayers file their tax returns the subsequent April, when drops in capital gains realizations and other capital income cause a sharp drop in collections from higher-income individuals. Whether that happens in this downturn is an open question given the quick rebound in the stock market and how this recession has disproportionately hit lower-income workers.

Revenues also typically decline in recessions because taxes are cut legislatively to help boost the economy; such tax cuts have been more limited so far in this downturn. By our measure, the effect of the payroll tax credits and other tax provisions enacted back in March did not have large effects in fiscal year 2020. The tax rebates in the CARES Act, enacted back in March, were large, but unlike with previous such rebates, the Treasury Department classified the effects of the rebate payments as increases in spending rather than as decreases in revenues. If those $275 billion in rebates had been classified as revenue reductions, revenues relative to GDP for 2020 would have dropped by about 1.3 percentage points to 15 percent of GDP. The budgetary classification of the rebates has no effect on the federal deficit, but it does make it more difficult to compare federal revenues and spending separately in this recession compared to previous ones.

Note that there are some tax cut provisions of the CARES Act, largely provisions allowing corporations and primarily higher-income taxpayers a greater use of business losses to reduce taxes, that could reduce revenues a substantial amount in fiscal year 2021. Further legislative action could also change tax payments going forward, although even the direction is unclear because recent House-passed stimulus legislation would roll back much of those provisions affecting the use of business losses along with providing other spending increases and tax reductions.