Posted on August 23, 2020

Summary

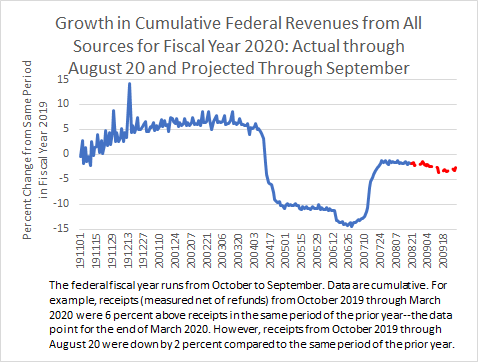

- We estimate that total federal revenues for the fiscal year-to-date, through August 20, are down by about 2 percent compared to last year’s amounts at this same point.

- Based on recent trends, we extrapolate that weakness in revenues in the remaining 5-1/2 weeks of the fiscal year will push revenue growth down by slightly more, with revenues declining for the full year by between 2 and 3 percent.

- The biggest wildcard we see still remaining is whether significant amounts of refunds will be paid out to corporations and individuals as a result of retroactive provisions of the CARES Act. The effects of the President’s executive action to allow deferral of employee Social Security payroll tax payments is not likely to move the revenue needle much at all in the remaining weeks of the fiscal year.

We know that growth in total federal revenues in fiscal year 2020 has been the story of two separate periods: up 6 percent from October through March (compared to the same period a year ago), and down 10 percent from April through July. Including some continued slippage in August, we estimate that total revenues are down by about 2 percent for the fiscal year through August 20 (see chart above). The payment delays allowed for filing federal income taxes and paying amounts due, along with delays allowed for quarterly estimated payments in April and June, caused receipts to fall well below year-ago levels through June, but then revenues came back in July with the end of many of the deferrals. With five and a half weeks left in the fiscal year, we extrapolate, based on recent trends, that revenues by fiscal year-end will be down by 2 percent to 3 percent, so not much different than for the year-to-date (see red, dotted line in above chart for the projection for the rest of the fiscal year). Is that reasonable? What are the big unknowns still left?

We can make seemingly pretty reasonable assumptions about the remainder of the fiscal year for income and payroll tax withholding (down 7 percent), corporate income tax quarterly payments in September (down 20 percent), and individual income tax quarterly payments in September (down 10 percent). Those declines are roughly how much we estimate that those revenues in recent months have fallen short of last year’s amounts. And going in the other direction, we can’t forget the health insurers’ excise tax, a leftover from the Affordable Care Act (aka Obamacare) that was not in effect in 2019, won’t be in effect starting next year, but does have one last payment due by September 30 this year that should boost total revenues by about half a percentage point or so. In any event, it would take some significant deviations from all of those values to move the needle a lot with so much of revenues this fiscal year already in the books.

The biggest wildcard seems to be corporate and individual income tax refunds. A smaller one, likely not to move the needle much at all, is the effect of the Presidential executive action to allow deferral, for most workers, of their portion of Social Security payroll taxes. (Any additional legislation enacted in coming weeks could also affect things, but it’s getting late for even that to have much effect this fiscal year.)

Starting with refunds, the CARES Act contained two retroactive business provisions that could result in very significant refunds at some point. We posted last week about our skepticism that those refunds could go out quickly enough to significantly affect revenues this fiscal year. If they did, however, that could have a significant effect on revenue growth. The Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) estimated back in March, at the time of enactment, that the two provisions–one allowing businesses (mainly corporations) to carry back losses in 2018, 2019, and 2020 for up to 5 years, and the other allowing individuals with certain large business losses in those same three years to use them to offset non-business income–would reduce revenues by a combined $155 billion in fiscal year 2020. Much has happened since enactment and perhaps JCT wouldn’t have the same estimate today. In any event, if even half of that total revenue effect (about $75 billion) hadn’t yet affected receipts and occurred all in the September, that would make the decline in total revenue growth for the year in our extrapolation closer to 5 percent.

Then what about the deferral of employee Social Security payroll taxes? It seems likely that the effects of the deferral will be very small in September, based on the fact that the Treasury Department hasn’t yet provided guidance with just one week until the starting date on September 1, and employers will need some time to reprogram their payroll systems, an especially difficult task given the mid-quarter change and the limit of the deferral to those workers earning less than $2,000 per week. And it isn’t even required for employers to take up the deferral option, and there has been much discussion about why many, indeed maybe most, won’t take up the option. Even if all employers did defer remitting those taxes to the Treasury, thereby increasing their employees’ paychecks for now, and they even somehow managed to get it all implemented by September 1, I estimate that it would still just reduce growth in total revenues for the full year by a little less than 1 percentage point. And the effect is likely to be much smaller than that.