Posted on September 6, 2021

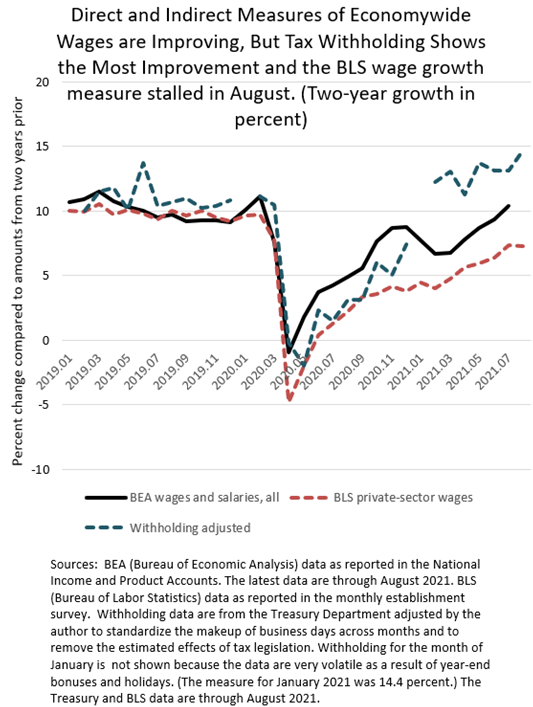

Happy Labor Day. It’s a good time to assess the state of the overall labor market, a few days after the employment report for August released by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) last Friday. The report showed an unexpectedly small increase in overall employment in August and weak wage growth. Compared to the amount in August 2019, private sector wages in the economy were up by 7.3 percent, a slight drop from the 7.4 percent two-year growth recorded in July (see chart below). At the same time, our measure of economywide withholding of income and payroll taxes moved up in August, registering nearly 15 percent two-year growth, compared to about 13 percent two-year growth in both June and July. Wages as measured by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) in the National Income and Product Accounts (NIPAs) for August don’t get released until the end of this month, but they are likely to follow the BLS data, at least until the data become available for them to switch to tracking the more comprehensive quarterly employer reports for purposes of the government administering the unemployment insurance system. (Those data for the the July-September quarter won’t be available until early next year.) The BEA’s NIPA wage data have been showing greater growth than have the data from the BLS monthly employment reports, but are still 3 percentage points or more below tax withholding growth, which normally tracks wages relatively well. So, what do we make of all this?

Withholding is being boosted relative to wages, we believe, because of shifts in the distribution of wages in the overall economy away from lower-income workers and towards higher-income workers. With a progressive income tax system in which individuals with higher income face higher tax rates, more income for higher income-workers and less for lower-income workers raises income tax withholding relative to wages. Although the wage and overall income distribution is well studied in the economics literature, it is hard to get real-time measures of distributional shifts. The best I’ve seen comes from the Opportunity Insights Economic Tracker, which is put together by a team based largely at Harvard University and led by Raj Chetty, John Friedman, and Nathaniel Hendren. From their valuable research they estimate that employment in late July among workers earning below $27,000 annually has fallen by over 22 percent since January 2020, while employment has risen for workers earning between $27,000 and $60,000 by 3.7 percent, and by 9.9 percent for workers earning more than $60,000 annually. They track the shifts on a near daily basis, and the shift away from lower-paying jobs has been occurring since the beginning of the pandemic. Now that’s jobs not wages. I have no separate information of how wage gains have been distributed per employed worker. While the recent shortage of workers able and willing to work at the lower-paying jobs has resulted in long-due wage gains for those individuals who are employed, higher-income workers are reportedly doing quite well, I see no basis for estimating that there has been a shift one way or the other in hourly wage gains across the income distribution.

Based on the Opportunity Insights estimates for employment, we estimate that the employment (and implied wage) distributional shifts are boosting overall tax withholding growth by between 1 and 1.5 percentage points above wage growth. That is based solely on the employment shift estimates, and doesn’t incorporate any changes in the distribution of average hourly wages, as described above. We have a model of withholding among different income groups that maybe we’ll describe and show at some point, but the results are that we estimate that income tax withholding is being boosted by about 3.5 percentage points above wage growth as a result of the distributional shifts. That’s a lot, but not the whole story, because total withholding also includes payroll taxes, which get skewed in the opposite direction relative to wages from distributional shifts because workers don’t pay Social Security payroll taxes on wages above $142,800 in 2021 (an amount that rises annually with average wage growth in the economy). We estimate that wage distribution shifts are reducing Social Security payroll tax withholding by about 1 percentage point relative to overall wages. Overall income tax withholding is just a bit larger than payroll tax withholding, and so the combined effect of the income and payroll tax changes from employment distribution shifts is our estimated 1 to 1.5 percentage point boost to total withholding growth relative to total wage growth. That would be a chunk of the observed difference between total withholding growth and wage growth in the NIPAs, but much of the difference would still remain. Some of the remainder could be real bracket creep, which tends to boost withholding growth above wage growth by about 0.5 to 1.0 percentage points in a growing economy–as additional wages earned by individuals (in excess of consumer price inflation) push a greater share into higher tax brackets. We still have work to do to understand the differences in the growth of withholding and wages, but wage and employment distributional shifts should be a significant part of the story.