Posted on August 14, 2020

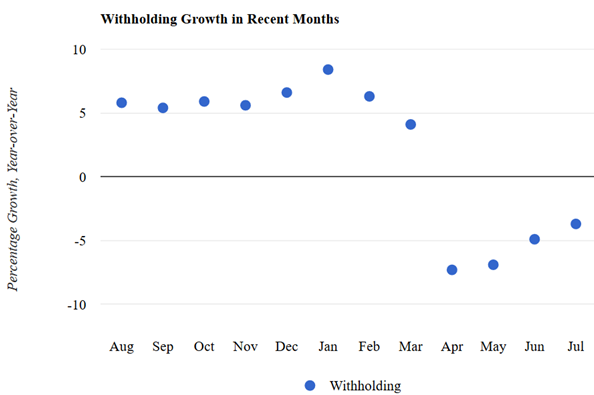

We posted last month about the anomalous surge in withholding tax remittances in mid-July, timed just as a large amount of delayed income tax payments were being remitted to the Treasury. We thought it quite possible that taxpayers didn’t correctly identify which taxes were being paid and that the Treasury Department would fix up the allocations in mid-August in the Monthly Treasury Statement. Well, there was no correction in the Monthly Treasury Statement for July released earlier this week. The month-to-month change in the withholding growth rate–from a decline of 4.9 percent (year-over-year) in June to a slight increase of 0.3 percent in July, a swing of 5.2 percentage points–is large enough that our outlier recognition kicks in and we ignore that observation for purposes of measuring July growth and instead use the growth rate for the first half of July, which was a decline of 3.7 percent (see chart below). It is not credible that wages, the main determinant of withholding, jumped so much in July, considering the state of the economy. (Note that all withholding growth rates cited remove the estimated effects of law changes that affect withholding but not wages and salaries, in order to measure the movement in constant law withholding that should line up more closely with wages and salaries.)

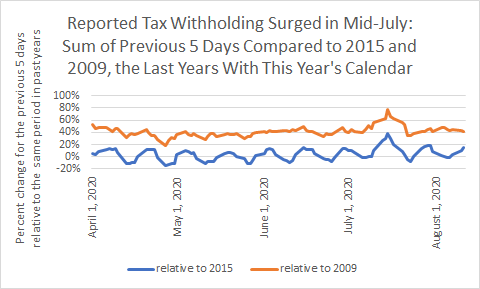

Identifying when the surge in withholding occurred is apparent by comparing daily receipts to those made in 2009 and 2015, which had the same calendar as this year (after leap year February this year). Payments by day are so variable that it is difficult to compare to last year’s amounts if the calendars are at all different. Payments in mid-July 2020 (a five-day moving average) rose 80 percent above 2009’s level and 40 percent above 2015’s level for the same period, after never being close to that high since the pandemic began (see chart below). And since mid-July, withholding has moved back down much of the way by those metrics. There is evidence of some continued strength in withholding in the comparison to 2015, and extrapolations of the daily withholding data suggest that withholding could still be somewhat strong throughout this August, though clearly it is difficult to extrapolate.

Another way of identifying an anomalous observation is to compare it with other measures with similar characteristics. For that, we go to the BLS employment report, which uses a sample of establishments to identify employment and pay amounts. The results for July, released in early August, showed economywide private sector wage growth, year-over-year, improving some in July, to a decline of 3.1 percent from a decline of 4.2 percent in June. An improvement, but not like that suggested by the withholding data that includes the mid-July remittances. Indeed, the movement in private sector wage growth is more like the growth in withholding for July with our substitute value using the information from the first half of July.

Discarding economic data, even when seemingly anomalous, is very undesirable, especially when the source of the anomaly is unknown. We never discard data on withholding growth for the months of December, January, and February, which can be quite volatile because of the effects of year-end bonuses. For the other nine months, we’ve never had such a one-month swing up in withholding growth as we saw in July. It is big enough that it is the only such observation over the 2005-2020 period for which we use a substitute measure. The only other time there was such a swing, in the downward direction this past April, was due to the well-known effects of the pandemic and stay-at-home orders, so we did not substitute for that observation.

So, why could the reported amounts of withholding in July have been anomalous? Since we don’t have access to the employer-by-employer payments, we’ll probably never know why. Possibilities that come to mind include: 1) firms made misallocations when reporting their payments, ones that the Treasury Department has yet to identify; 2) something very quickly changed in the effects of recent legislation, although nothing so abrupt seems likely; 3) a big firm made corrections to its previous withholding amounts, but no one firm would likely be large enough to move the totals that much; 4) withholding in July of 2019 was unusually low, but there is no evidence of that; 5) random noise, although, as stated, this was ahistorically large.

One thing I do know: I don’t have the patience to wait until July 2021 to see if withholding growth relative to July 2020 takes a big step downward from what we would otherwise expect.