Posted on March 2, 2020

The IRS has released data on tax refunds through week four of the filing season, and the dollar amount of refunds is down 3.4 percent from last year’s amount at this same point There are certainly signs that refund growth could be very low this year, or perhaps refunds could even drop some from last year’s amounts (as they did last year compared to two years ago). Normally almost half of refunds have been paid out by now, so we are getting to the point where the story is beginning to gel.

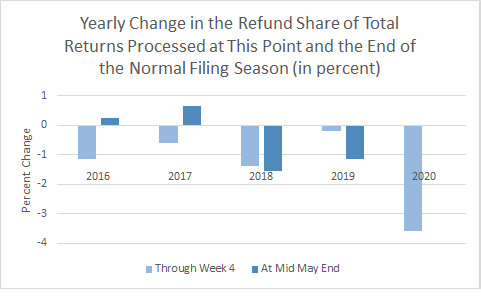

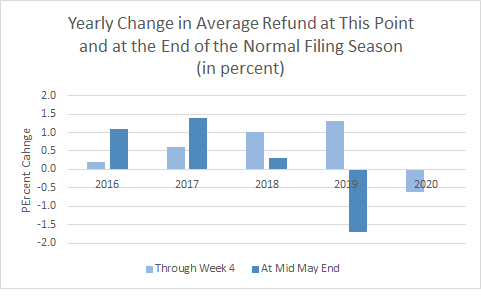

The total dollar amount of refunds is down through week four this year (compared to the same point last year) both because the average refund is down (by 0.6 percent, see first chart) and the number of returns with refunds is down (by 2.9 percent, see second chart). The combination of those two factors algebraically explains the total dollar amount being down (by 3.4 percent, roughly the sum of the two pieces.) (Sorry, there are logarithms and compounding involved, but the sum of the two percent pieces is a close approximation of total percent changes for small, single-digit percent changes.)

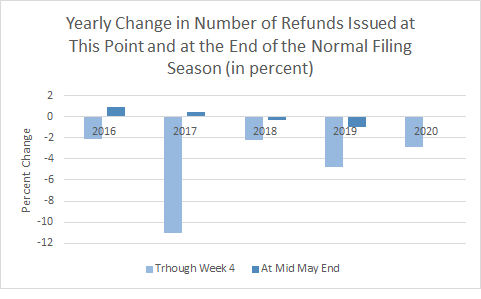

My former colleagues at the Congressional Budget Office heard me say all too often to focus on the average refund, not the number of refunds. The percent change in the number of refunds almost always eventually, by the end of filing season, moves to a small annual increase or decrease of a percent or so at most (again, see the second chart). About three-quarters of taxpayers get refunds, and that hasn’t changed much over the years. Why worry about the deviations earlier in the filing season? The average refund, though, can be up or down by more, and the early results can be much more persistent.

Average refunds are down slightly so far this season, but I could see them rising some by the end of the normal filing season in mid May. (The full filing season continues into October for taxpayers filing for extension.) Last year the growth in the average refund abnormally dropped a lot between week 4 and mid May (from a gain of 1.3 percent to a drop of 1.7 percent), and that abnormal movement could indicate some temporary timing shift that will get undone this year. It could also indicate, however, that the early filers had a different effect from the tax cuts enacted in December 2017 than did the later filers, and that could continue into this year.

In the other direction, for a change of pace I’m wondering if the number of returns with refunds could actually change by more than normal (meaning my rule of focusing only on average refunds may be wrong). Indeed, it seems possible that the number of refunds could drop by a couple of percent or so this season. The reason is that the share of returns with refunds has dropped much more than normal at this point, and at this point that percentage change tends to change only a little by the end of the filing season (see third chart below). The number of refunds can be down a lot at this point in the season, but it has historically been because the number of returns processed was down. But this year the number of refunds is down even though the number of returns processed is up slightly. It could, though, be a temporary timing blip. It is perilous using the data on number of returns processed, because the IRS can hold up refund payments even after processing, such as is mandated early in the filing season for returns claiming the earned income credit and refundable child credit (which should no longer be affecting things, see earlier post), or for other reasons including changes in IRS fraud filters. So, we need more information.

Although the data suggest that it is possible that the overall dollar amount of refunds could be down this year (compared to last year’s amounts) when all is said and done, it’s hard to posit reasons why. Yes, last year, many people had refunds lowered or eliminated by the updated withholding tables implemented in 2018 following the tax cuts enacted in December 2017–when in many cases their withholding cuts exceeded their tax cut–and in 2019 the new tables were in effect for all 12 months instead of 11 months or so in 2018. The updated withholding tables affected refunds significantly last year, but an additional month of the lower withholding in 2019 shouldn’t make much difference in refunds this year. The lack of good, underlying (that is, non-timing) reasons for a nontrivial drop in refunds at this point in the filing season may mean everything will come more into alignment as the IRS processing continues. Stay tuned.