Posted on November 23, 2021

Happy Thanksgiving Week to everyone. New data on tax collections in November are somewhat sparse, with no major quarterly payments due from individuals or corporations, and with no payment deadlines for final payments with tax returns. Mostly November tax collections consist of income and payroll tax amounts withheld from paychecks. However, each November we do get partial information from the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW) on economywide wages and salaries paid in the second quarter, so from April through June. Although not extremely current, those data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) are high quality because they come from administrative sources–that is, they come from data nearly all employers are required to report (in this case, for purposes of states and the federal government administering the unemployment insurance system), rather than from a survey of employers such as the monthly establishment survey that BLS also releases and that moves markets generally on the first Friday of each month. The amount of wages and salaries in the economy are important because they are a good gauge of overall economic conditions, which is important for the Federal Reserve’s decisions on monetary policy, and because wages and salaries are the base of most tax collections, which is important for the overall federal budget.

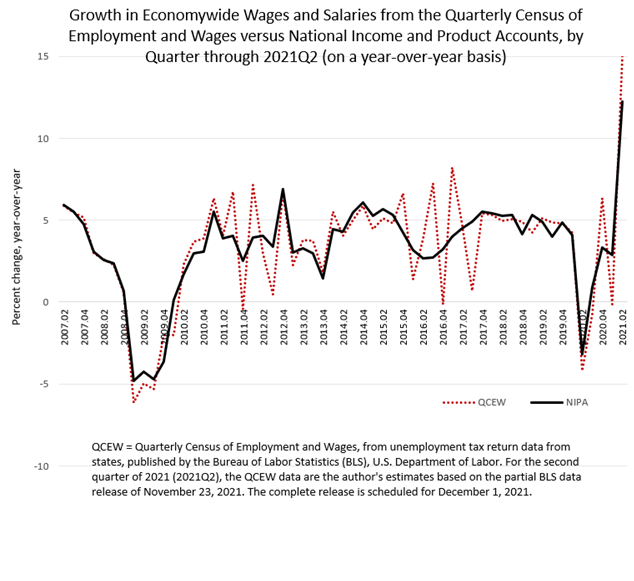

Today’s partial QCEW release–the full release comes on December 1–suggests that wages and salaries in 2021Q2 are roughly in line with amounts currently measured in the National Income and Product Accounts. The amounts from the QCEW grew by about 15 percent in the second quarter of 2021 compared to the second quarter of 2020 (a so-called “year-over-year” basis), about 3 percentage points more than the 12.3 percent growth currently in the National Income and Product Accounts (see chart below). But that difference doesn’t seem significant. The QCEW data are high quality but very volatile because of the way the data are collected: a different number of business days or paydays in a quarter compared to the same quarter in the prior year can cause anomalous jumps or drops in the data. In the first quarter, the QCEW data measured wages and salaries as growing about 3 percentage points less than the amount from the NIPAs. That 3-4 percentage point difference has occurred at various points throughout the history of the series, and would be equivalent to less than one major payday in 13 weeks falling in or out of the period.

So, it’s hard to draw conclusions from such volatile quarterly data, but we aren’t expecting to see any major revisions to the National Income and Product Accounts (NIPAs) for the second quarter in tomorrow’s release. The QCEW data, when they become available, are used by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (which estimates wages as part of the NIPAs) to update their measure of economywide wages. In any event, we have posted before how withholding of income and payroll taxes from paychecks and remitted daily to the U.S. Treasury, which is highly dependent on the amount of economywide wages and salaries, has been growing much faster than both NIPA wages and salaries and those compiled from the BLS monthly establishment report. We don’t expect that story to change as a result of the new QCEW data being incorporated into the NIPAs. Assuming that is the case, we would continue to argue that withholding tax collections are well outpacing the economywide measures of wages because growth in wages through the recession and recovery has been concentrated in higher-income taxpayers who face the highest tax rates and pay the bulk of income and payroll taxes.

The QCEW data become more valuable when they cover the full calendar year, after which all the timing quirks with paydays largely average out and we can get a very good picture of wages for the full year. That allows us to get a very good handle on upcoming NIPA revisions and even allows us to estimate fairly well the national average wage index for Social Security, an important measure for calculating a worker’s initial Social Security benefits and the maximum amount of a worker’s wages and salaries subject to the Social Security payroll tax.