February 24, 2021

Summary

- Partial data for 2020Q3 from the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW), released today by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, indicate a possible upcoming downward revision, perhaps on the order of 1.5 percent, to wages and salaries in the National Income and Product Accounts (NIPAs) for the quarter. The NIPA data are released tomorrow.

- We’ll look at the full QCEW report for 2020Q3, to be released during the second week of March, to assess the potential 2020 Social Security average wage index. At this point, it looks even more likely than before today’s release that the national average wage index will be falling some in 2020, but not nearly as much as feared during the worst of the downturn last year. That has significant impacts on future Social Security beneficiaries, especially those who turned 60 in 2020.

Every five months the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) releases quarterly data on employment and wages for the quarter ending about five months before. Today BLS released a report for 2020Q3, although as always it is incomplete initially; the complete report will be available in the second week of March. These BLS data eventually form the basis for the National Income and Product Account (NIPA) measures of wages and salaries, which are temporarily based on a different BLS source, the monthly establishment survey, until these data from the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW) are available. The QCEW data are valuable because, unlike the monthly establishment survey, they are based on administrative records—reports required to be filed by most all employers for purposes of the states and federal government administering the unemployment insurance program. The NIPA data, once revised when the QCEW data become available, correlate highly with other economywide wage measures, such as those that determine the average wage index for Social Security purposes.

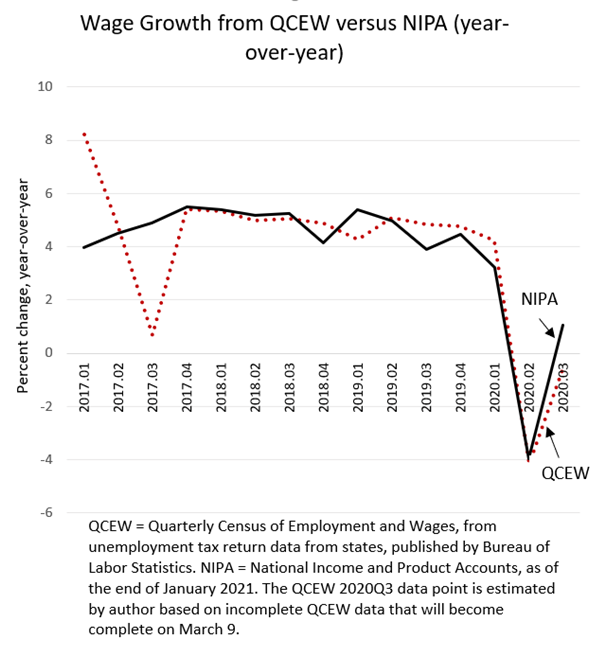

Today’s QCEW release indicates the possibility of a downward revision to NIPA data for 2020Q3, perhaps on the order of 1.5 percent. NIPA wages for the third quarter of 2020, estimated as of the end of January, grew at about 1 percent above the 2019Q3 amount, but the QCEW data, by my estimate (after filling in the missing employment components for the first two months of the quarter with information from the monthly establishment survey) fell by about 0.5 percent on that same year-over-year basis (see chart below). Since the NIPAs are revised tomorrow, that takes away some of the anticipation. We can usually tell why such NIPA revisions are as they are once the full QCEW data are released the following month; the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), which puts together the NIPAs, has the complete QCEW report available in advance.

There are two sources of uncertainty with my estimate for a downward NIPA revision. First, my estimates for the missing employment months in the initial QCEW report could be off. The second, bigger source of uncertainty is that the QCEW and NIPA amounts don’t always line up on a quarter-to-quarter basis. They generally are pretty close, but there was a big deviation in the first and third quarters of 2017, for example. The QCEW and NIPA line up very closely on an annual basis, once the NIPAs are revised for conformity, but the quarterly amounts from the QCEW are subject to calendar differences between years much like the tax withholding data that we analyze. When the NIPA estimates are constructed, BEA adds on some relatively small components not included in the QCEW data but also seasonally adjusts the data, and that seasonal adjustment can lead to occasional disjoints such as in 2017. Those disjoints average out over the full year.

We plan to look at the final QCEW data released next month to see what the implications are for the Social Security national average wage index, which determines the next year’s Social Security taxable maximum amount and, especially for 2020, is very important for the calculation of the initial Social Security benefits for a retiree. The past year’s recession has had the potential to significantly lower the starting (and therefore lifetime) benefits for people turning 60 in 2020 (see previous post). The problem for those individuals doesn’t look to be anywhere near as dire as originally thought, as wages bounced back in 2020 more quickly than expected, but the QCEW data for 2020Q3 seems to make it even more likely than before that there will be a downward movement in the average indexed wage for 2020. More on this later.