Posted on January 7, 2022

Summary

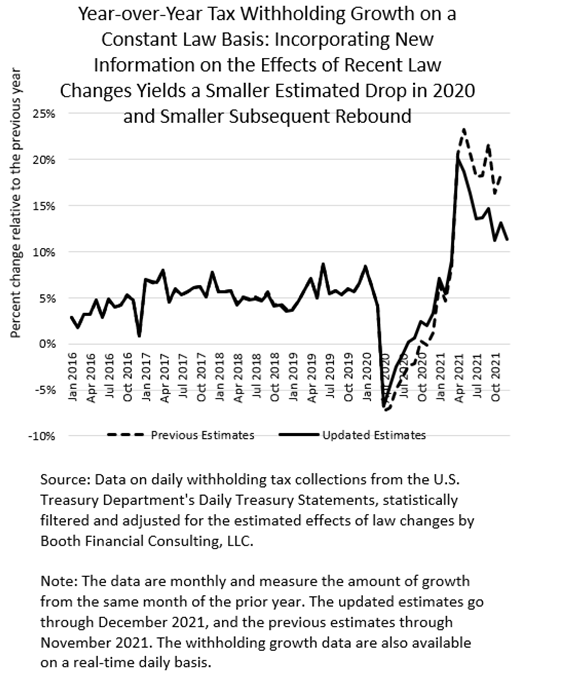

- We have revised our estimates of constant law tax withholding growth on a year-over-year basis (that is, removing certain legislative effects and comparing amounts in a month with those in the same month a year ago) to incorporate new information on the effects of tax law changes enacted in 2020.

- In particular, based on estimates published by a Treasury Department economist, we now attribute more of the decline in withholding remittances in the spring and summer of 2020 to the provision allowing firms to defer payment of their share of the Social Security payroll tax, and we attribute less of the decline to underlying withholding (what we call constant law withholding, or withholding absent law changes). The changes work in the opposite direction in 2021.

- For most of 2021, we concentrated our analysis on two-year growth in withholding, thus looking back before the pandemic for which the effects of the tax law changes enacted in 2020 play only a limited role. But now, with better information in hand, we can start looking again at the percentage changes on the more conventional year-over-year basis.

- For all of our historical estimates back to 2005 of underlying withholding growth, we have used estimates of the effects of legislation available around the time of enactment; thus, no later revisions were necessary. This is the first time we’ve used information on legislative effects available substantially after enactment. Revising the data on withholding growth absent law changes works against the usefulness of the withholding data, whose main advantage is that they are available so quickly while still giving a good approximation of movements in wages if distilled properly.

- We are making available, in spreadsheet form, the updated estimates of daily and monthly withholding growth back to mid-2019. Data before that are available for a charge.

The good news is that we are feeling more comfortable measuring recent tax withholding growth, adjusted to remove the effects of law changes, on a year-over-year basis–that is, measuring growth over the past year. However, we are more comfortable because new information about the tax effects of recent law changes has led us to revise the estimates through the recent recession and recovery. Since last spring, we’ve been looking at withholding growth on a two-year (not one-year) basis, that is, measuring growth back to before the pandemic, specifically because we were unsure of the effects of recent tax law changes. Stepping back, in an effort to make the tax withholding data more usable in tracking overall wages and salaries in the economy, we remove the estimated effects of tax law changes that affect withholding but not wages and salaries. That adjustment works fine except when significant and difficult-to-estimate tax law changes are put in place like in 2020. But now we have much better information of the effects on withholding of the 2020 CARES Act–which has caused us to measure underlying tax withholding (that is, on a constant law basis that removes the estimated effects of law changes) as falling somewhat less in the recent recession and recovering at a slower pace since then (see chart below).

Most importantly, we have increased the estimated revenue loss for 2020 from the payroll tax deferral provision enacted in March 2020 in the CARES Act. Based on information published in a working paper by Treasury economist Lucas Goodman, who had access to confidential tax return data, we now estimate that the payroll tax deferral option, along with other less significant payroll tax credits included in the legislation, reduced withholding growth by about 7 percent in the last nine months of 2020, rather than the 4 percent to 4.6 percent we had been estimating. Thus, when we observe actual withholding falling in the spring and summer of 2020 (relative to the amount in the comparable periods of 2019), we now estimate that there was a smaller decline in underlying withholding (what we call constant law withholding) and more of a decline from the legislation. Similarly, in 2021, when the deferral provision was no longer in effect and the overall economy improved, we now attribute less of the withholding growth to underlying movements in withholding and more to the absence of the deferral provision. (The deferral provision reduced withholding in 2020 but not in 2021, thus causing a jump in withholding growth in 2021 compared to 2020. Half of the deferred amounts were required to be paid by no later than December 31, 2021, and the other half by December 31, 2022, but that’s another story that we covered in our post earlier this week.)

The legislative estimates were the most significant cause of the change in our constant law (that is, underlying) withholding estimates, but we also made some other changes. With the larger drop in withholding attributed to legislative factors, we modified our calculations to more precisely break out the underlying and legislative components of observed withholding growth. We had previously simply estimated the constant law growth rate by taking the observed growth rate and subtracting the estimated growth rate effect of the law changes. (For example, if observed [that is, actual] withholding growth was 7 percent, and we estimated that the law change added 7 percent to withholding, then we would estimate that underlying withholding growth was zero.) That simple formula is a good approximation for small percentage changes, but not when the changes become larger and especially in opposite directions. (It’s the old issue that, for example, a 50 percent drop followed by a 50 percent increase, measured relative to the lower level, don’t get you back near the starting point.). Now we use the proper multiplicative formula to break out the components. We also identified a way to estimate withholding growth for an extra day or so in the first half of many months, but those are few and far between and have little effect on monthly totals.

Revising our estimates of withholding growth works against the real-time usefulness of the data. The withholding data are especially useful because they provide a real-time signal of movements in overall wages and salaries in the economy. Big firms are required to remit their income and payroll tax withholding to the Treasury the day after they pay their workers, and then the Treasury makes public the aggregate amount paid the day after that. That process yields a very current measure of withholding and, by inference, wages and salaries. But if the withholding data as we measure them get revised later, that reduces the real-time advantages of the data, because all sorts of data on wages become available in the weeks and months following the payment of wages to workers. In fact, for our historical measures of withholding growth adjusted for law changes (our data go back to 2005), we’ve always used estimates available at the time of enactment of the law changes–thus never needing revision when later information became available. The effects of law changes affecting withholding have typically been relatively straightforward to estimate; for example, changes in tax rates, which have been the most prevalent type of change historically, are not difficult to model and estimate. But the CARES Act was designed to provide funds quickly to businesses, and policymakers discovered that providing deferrals and tax credits applied to withholding could quickly get funds to businesses–or more precisely allowing them to keep funds, at least temporarily, that they would otherwise send to the federal government as tax payments. The take-up by firms of those provisions was very difficult to predict. The initial Congressional budgetary estimates far overestimated the share of firms that would take up the option to defer the payroll tax withholding, and for our purposes, we cut those Congressional estimates way down; but it is now clear that we overshot–hence our revisions.

Our estimates of withholding back to the summer of 2019, both before and after our revisions, are available in spreadsheet form here [and subsequently corrected estimates here as of January 11 that changed the amounts for January 2021 slightly]. We include both the daily estimates and the monthly aggregation. The revised data before that are available for a charge. Please contact us if you are interested in obtaining that data. See our methodology page for how we compile the data.