Posted May 21, 2021

- We estimate from partial data for 2020Q4 from the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW) that economywide wages in the quarter grew very fast, 6.2 percent above the amounts from 2019Q4, largely because of a very large increase (13 percent) in average wages in the economy.

- The high growth in economywide wages that we estimate from the QCEW suggests that wages and salaries as measured in the National Income and Product Accounts (NIPAs) will be revised up for 2020Q4, perhaps by a very large amount, as much as 5 percent, when the next NIPA release comes out next week. That would be a very large revision and is uncertain for several reasons. A smaller upward revision seems more likely.

- We’ll look at the revised NIPA data released next week and the full QCEW data released the following week to assess the potential 2020 Social Security national average wage index. A substantial upward revision to NIPA wages would make it more likely that the national average wage index will rise somewhat for 2020, unlike expectations last year for a potential large drop in the index, and more modest decreases more recently projected by experts. An increase would be good news especially for future Social Security recipients who were born in 1960.

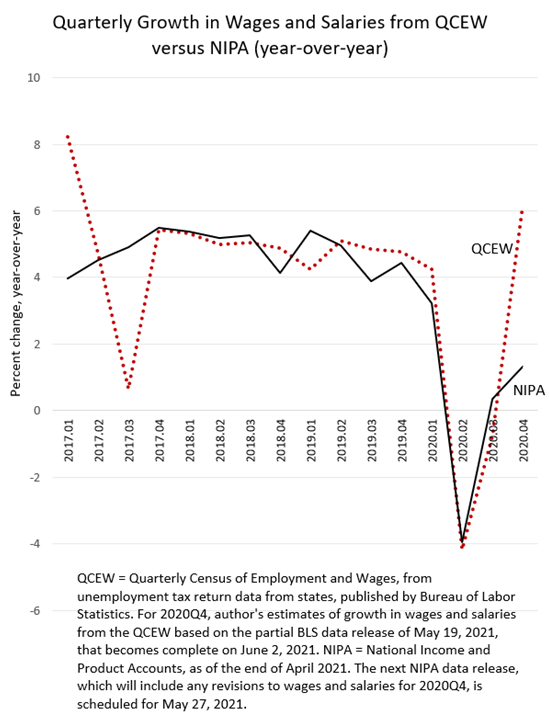

It looks from the release on Wednesday of this week of certain data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS, in the U.S. Department of Commerce) that wages and salaries are going to be revised up for the fourth quarter of 2020, perhaps by a lot. Specifically, BLS released a partial amount of data from the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages for 2020Q4; every five months BLS releases the data for the quarter ending five months earlier. As always, the report is incomplete initially, and the next complete report is scheduled for release on June 2. But based on the incomplete data, we estimate that economywide wages and salaries as measured in the QCEW were 6.2 percent higher than in the fourth quarter of 2019; that is a lot higher than the 1.3 percent increase that is currently being measured for wage and salaries in the National Income and Product Accounts (see chart below). Historically, the two measurements tend to line up, which is not a surprise because the QCEW measure of wages and salaries eventually forms the basis for the NIPA measure, which in the meantime is based on a different BLS data source, the monthly establishment survey. The QCEW data are valuable because, unlike the establishment survey, they are based on administrative records–reports required to be filed by nearly all employers in order for the states and the federal government to administer the unemployment insurance program. Administrative records generally are far superior to surveys because they are much more comprehensive and penalties can apply for inaccurate reporting.

So, could the QCEW data be telling us that we will see a substantial NIPA wage revision next week of upwards of 5 percentage points for 2020Q4? That would be a very, very large revision. If it occurred, or a (more likely) smaller yet still substantial upward revision, it would have implications not only for understanding the path of recovery of economywide wages, but also for the national average wage index for 2020 that is very important for new Social Security recipients.

One thing that gives me pause in interpreting the QCEW data for 2020Q4 is that they just look so much stronger than other indicators of wage growth, and the strength is based on extremely fast and difficult to understand growth in average wages. BLS-measured total private-sector wages from the establishment survey fell by 0.4 percent in 2020Q4 (compared to the same quarter in 2019), and our website’s measure of withholding growth, adjusted for law changes, was just about unchanged in 2020Q4. That’s much different than the 6.2 percent growth I estimated from the QCEW. The QCEW measures that average wages rose by 13 percent in 2020Q4 relative to 2019Q4–that’s directly from BLS, not my reading of the data; why average wages would rise so much is a bit of a mystery. We saw average wages in the establishment survey jump way up last spring, at the beginning of the recession, as lower-income workers were much more likely to lose their jobs–a mix effect boosting economywide wage amounts on average for those still working. To some extent that higher average wage has continued throughout the recovery. But a 13 percent year-over-year increase in average wages in 2020Q4–which together with a 6 percent or so drop in employment yields the 6 percent estimated increase in QCEW total wages–seems high and must be more than just a mix effect.

If NIPA wages are revised up substantially next week for 2020Q4, that would increase the likelihood that the national average wage index (AWI) for Social Security will be measured by the Social Security Administration (SSA) to have increased in 2020. (SSA will tabulate W-2s issued by employers and then announce the results probably in October.) We have posted previously about the likely movement in the average indexed wage in 2020 (see post). We plan to look at the revised NIPA data released next week and the final QCEW data released the week after that to see what the implications are for the Social Security national average wage index; the index determines next year’s Social Security taxable maximum amount and, especially for 2020, is very important for the calculation of initial Social Security benefits for a retiree. The past year’s recession has the potential to significantly lower the starting benefits for people born in 1960, but the problem is looking less and less dire than originally thought. If NIPA wages were revised up by a full 5 percentage points for 2020Q4, a very large revision, that would push up annual wage growth in 2020 to about 1.5 percent (from the 0.2 percent currently estimated for the year in the NIPA data). Combined with what I infer from estimates released by the Congressional Budget Office that the number of people employed at any point in 2020 rose by 0.8 percent (again, see the earlier post), that would make my estimate for the average wage index an increase of about 0.7 percent. Smaller upward revisions to 2020Q4 NIPA wages, I think a more likely outcome, would imply smaller increases in the AWI. Smaller increases in employment or outright declines, however, would boost the AWI. But I am only conjecturing at this point.

All of this is based on my reading of QCEW growth in 2020Q4, which is uncertain for two reasons beyond my earlier mentioned difficulty understanding the very large increase in average wages. First, the QCEW and NIPA growth rates for wages don’t always line up on a quarter-to quarter-basis. They generally are very close, but there were big deviations, for example, in the first and third quarters of 2017 (again, see the chart). Those quarterly deviations, however, have averaged out over the full year, and for the past decade or more the full-year QCEW and NIPA wage growth measures have been nearly identical. Whether 2020 will be different because of difficulties in measuring economic activity during a pandemic remains an element of uncertainty. Secondly, and I think less significantly, in deriving the QCEW wage amounts I have to estimate employment for the first two months of the quarter; the initial QCEW release includes employment amounts only for the final month of the quarter. Nonetheless, I don’t think that uncertainty is large: the QCEW percentage change in employment in December, a decline of 6.1 percent compared to year-ago amounts, was just about the same as reported in the BLS monthly establishment survey for all private sector workers, and in earlier months through the downturn in 2020 employment moved similarly in both measures as well. So, I estimated October and November employment in the QCEW to follow that from the establishment survey as well.

We hope to have more to say on any NIPA wage revisions after the updated NIPA estimates are released on Thursday of next week.