Posted on December 10, 2021

Summary

- We expect that withheld amounts of income and payroll taxes remitted to the Treasury Department will jump in late December as a result of the payment of payroll tax amounts that were allowed by last year’s CARES Act to be deferred. The Act allowed payment of those amounts to be deferred in part to the end of this year and in part to the end of next year.

- Estimates of the overall deferred amounts based on confidential tax return data were released recently in a paper by a Treasury Department economist. Those estimates were relatively large, implying that the payments should stand out among the overall withholding amounts that we observe late this month.

- Withheld amounts late this year could also be boosted by strong year-end bonuses on Wall Street and elsewhere.

- The payment of the deferred payroll taxes are not related to the state of the current economy, but just represent a timing shift of amounts that otherwise would have been paid between late March and December 2020.

- The amount of the deferral appears to be significantly larger than we anticipated based on our reading last year of financial statements. The new information will cause us to soon raise our estimates of withholding growth in 2020 on a constant law basis. It doesn’t cause us to change our assessments of recent two-year growth in withholding, which we have been focusing on in part because of the uncertainties of the effects of last year’s law changes.

Among the many provisions of the CARES Act that were enacted in March 2020, employers were allowed to defer remittances of the employer half of the Social Security tax for an extended period of time. The deferral covered tax amounts due from wages paid from the end of March 2020 through December 31, 2020, with half of the deferred tax amounts required to be remitted to the Treasury by the end of calendar year 2021 and the other half by the end of calendar year 2022. The employer half of the Social Security payroll tax–so half of the 12.4 percent total tax rate, or 6.2 percent–is assessed on each employee’s earnings up to the annual taxable maximum amount, which was $137,700 for a worker last year. In recent years the employer half of the Social Security tax has accounted for roughly 17 percent of total withholding, which also includes income taxes withheld from paychecks as well as Medicare payroll taxes that are withheld from employees’ paychecks and supplemented by the employer’s share.

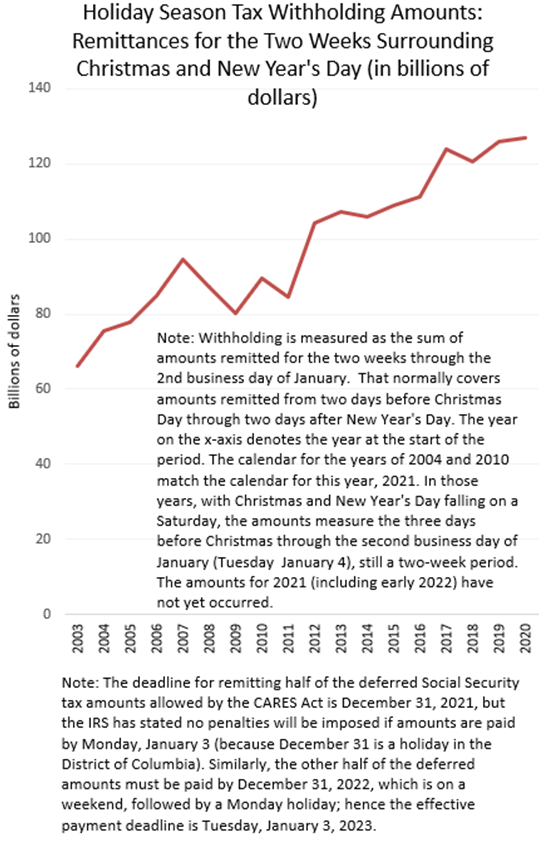

In a recent working paper published by a Treasury Department economist, Lucas Goodman, he estimates that the deferred payroll tax payments totaled about $126 billion in the last three quarters of 2020, or about 7 percent of total withholding over the period. Thus many employers, especially large ones, appear to have utilized the deferral opportunity, and we should expect a big amount of payments late this month as up to half of the deferred amounts are paid back. The payments won’t be separately identified in the publicly-released data; as always we’ll just see the overall amounts of daily withholding remittances, but if employers pay half of $126 billion, that would be over $60 billion, which would certainly be large enough to stick out in the overall data. In each of the past four years, between $120 billion and $127 billion of withholding was remitted to the Treasury in the two weeks surrounding Christmas and New Year’s Day, the reference period we are using for the likely time when those payments will be made (see chart below). There are some reasons why we expect the deferred payment this year to be a bit less than $60 billion, but we expect overall tax collections to be significantly goosed by the deferred payments. Note that these payments are totally unrelated to the state of today’s economy, being just a timing shift of amounts that would otherwise have been paid during the last three quarters of calendar year 2020.

Normally we assess late December withholding amounts with an eye to year-end bonuses, which can cause amounts to jump around significantly, as well as to impending law changes that can cause timing shifts between years. During the financial crisis in late 2008 and 2009, Wall Street bonuses and other incomes were hit hard and withholding dropped in late December (again, see the chart above). As for impending tax law changes, we observed a jump in withholding amounts in late December 2012, as taxpayers accelerated income into 2012, just before higher income tax rates for higher-income taxpayers began on January 1, 2013. Wall Street bonuses are expected to be strong this year, as the stock market has boomed and reportedly a record amount of private-equity deals and initial public offerings have taken place. That could boost withholding late this year even without the payment of deferred tax amounts. Increases in individual income tax rates don’t seem to be in the offing in the Build Back Better legislation that the Congress is working on, so we don’t expect any significant increase in withholding from income shifted from 2022 into 2021.

The Treasury Department economist, Lucas Goodman, looked at confidential tax return information from employers on the sources of their withholding payments, and assessed the 2020 deferred payroll tax amounts, which were separately identified–although they include presumably very small amounts from a separate optional employee Social Security tax deferral that covered the last four months of 2020, but which appears from the data to have had very small utilization. The amounts he found–over $40 billion in deferrals in each of the last three quarters of 2020 following enactment of the CARES Act–were about 25 percent larger than those reported by the General Accountability Office in a less complete assessment back in March 2021.

The deferral amounts that Goodman found were substantially larger than we expected based on our assessment in June of last year from financial statements; taking this new information into account, our adjustment of actual withholding growth for the effects of legislation will be updated in the near future, which will increase our estimates of year-over-year withholding growth, on a constant law basis, in the last three quarters of 2020, probably by a few percentage points after taking some other, partially offsetting new information into account. (Year-over-year growth compares amounts in a month with the same month in the previous year, a common way to measure changes in the economy in a way that avoids the distorting effects of comparing the amounts in unlike months.) Our estimates of 2020 year-over-year withholding growth on a constant law basis will be going up because more of the decline in actual withholding will be attributed to the deferral provision and less to underlying activity (the constant law measure). We adjust actual withholding for our estimates of the law change effects to get a handle on how economywide wages and salaries are moving; an actual (that is, unadjusted) withholding measure would not capture that underlying activity if withholding per dollar of wages were affected by legislation (see our methodology). The uncertainty of the effects of 2020 legislation is one reason why we’ve been focusing our assessment of withholding in 2021 on two-year growth, back to before the pandemic and the legislation passed in response; the two-year growth measures in recent months aren’t affected by what happened in 2020.

We don’t expect that the payments of the deferred withholding amounts in late December will be half of the deferred amounts that Goodman measures, because some firms have probably paid some amounts earlier than required. In particular, some firms that paid deferred amounts by mid-September 2021, will be able to take a tax deduction for the payments in calendar year 2020. That would allow such corporations with losses in 2020 to increase their losses and take advantage of another provision of the CARES Act, one that allows corporations with 2020 (or 2019 and 2018) losses to get refunds of income taxes paid up to five years earlier. That could be especially beneficial for firms that faced the higher corporate income tax rates that were in effect before 2018, because the deductions would be valued at the higher past tax rates rather than at today’s lower rates.

Along those same lines, we saw anomalously strong withholding in September 2021, and posted about that. Perhaps some of that unusual strength was from firms paying back the deferred payroll tax amounts earlier than necessary. The unexplained growth was only $5 billion to $10 billion at most, so if all of that was from deferred payroll tax payments, we would still expect a large payment in December this year. It is, of course, possible that some firms have been paying back deferred amounts through the course of 2021, but considering the trouble they went to in modifying the withholding amounts for their employees and the continued benefit of delaying payment, we don’t expect that earlier payments were common.

We’ll find out soon enough if withholding jumps up in the period from late December to the beginning of January. Although the due date for the payments specified in the CARES Act is December 31, for those of you who follow the calendar closely, December 31 this year is on a Friday and is a holiday in the District of Columbia; as a result the IRS has extended the deadline for the deferral payment to Monday, January 3, 2022. We also want to see the amounts employers pay on January 4 before we close the books on the period when those deferral payments should be made. We learn about the overall size of withholding the day after firms remit the amounts to the Treasury, and most withholding is remitted the day after firms pay their workers, so we find out quickly. Then there’s another payment of those deferred taxes, perhaps of like magnitude, in December 2022.